Racism, economic stagnation, and political polarization have gripped the continent. Elections have been manipulated, false promises made, scapegoats blamed. Government-run facilities are built to punish, deter, and house specific groups of people; there is chillingly little transparency regarding what occurs within. The passivity of citizens in the face of cruelty is duly noted. There is a sense that something grave and irrevocable is about to happen.

The year is 1938, and events are escalating in Europe. The Anschluss comes in March, the Munich Agreement in September. Construction at Dachau is completed in mid-August. Kristallnacht occurs on November 9th and 10th. In the words of Hermann Göring, “The Jewish problem will reach its solution if, in anytime soon, we will be drawn into war beyond our border – then it is obvious that we will have to manage a final account with the Jews.”

Elsa Barraine, a twenty-eight-year-old composer with a passion for politics, watches anxiously from France. She is devastated by what is unfolding. She is Jewish on her father’s side. Her reaction to Hitler was to join the French Communist Party. She has even penned a symphonic poem protesting fascism: 1933’s Pogromes. Its inspiration was a poem by Jewish poet André Spire. The first part of the poem encourages Jews to fight back against their enemies. But the second – and the only portion of the text that Barraine chooses to treat – chronicles the perspective of Jewish elders, who counsel acceptance of fate when confronted by inescapable destruction.

In 1938, as Nazism creeps closer to her doorstep and a global conflagration becomes inevitable, Elsa Barraine writes her second symphony. It is a work of majestic dread and determination, seasoned by hard jolts of violence and sarcasm. She entitles the work “Voina”: the Russian word for war.

France surrenders to the Nazis in June of 1940. On 7 December 1941 Adolf Hitler issues what becomes known as the Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) directive, targeting activists. That same day Heinrich Himmler issues clarifying instructions to the Gestapo:

After lengthy consideration, it is the will of the Führer that the measures taken against those who are guilty of offenses against the Reich or against the occupation forces in occupied areas should be altered. The Führer is of the opinion that in such cases penal servitude or even a hard labor sentence for life will be regarded as a sign of weakness. An effective and lasting deterrent can be achieved only by the death penalty or by taking measures which will leave the family and the population uncertain as to the fate of the offender. Deportation to Germany serves this purpose.

*

Elsa Jacqueline Barraine was born 13 February 1910 in Paris. Every member of her family was uncommonly musical. Her father Mathieu was the principal cellist of the storied Orchestre de l’Opéra, and her mother Octavie gave piano lessons and sang in the chorus of the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, one of the most prominent French orchestras of the era.

Her parents and her sister Agnès (fourteen years her senior) all contributed to Elsa’s musical education in their own ways. Her father brought her to rehearsals and performances at the decadent Palais Garnier opera house (the setting for the 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera). Octavie taught Elsa piano, while Agnès took her to harmony classes at the Paris Conservatoire. Elsa entered the Conservatoire at the age of nine. As a result, she received very little general education as a child, an insecurity that would bother her throughout her life.

She studied alongside soon-to-be-famous French composers including Yvonne Desportes, Maurice Duruflé, Claude Arrieu, and Olivier Messiaen. Even among these stars, she was a standout. At the age of fifteen she snagged a first prize in harmony. Two years later she won first prizes in fugue and counterpoint, as well in as piano accompaniment.

Elsa Barraine with her classmates. She’s at the left crossing her arms and her ankles.

Her mentor and dearest inspiration was her teacher Paul Dukas, best known today for writing the symphonic poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. He once declared that his goal as a teacher was “to help young musicians to express themselves in accordance with their own natures. Music necessarily has to express something; it is also obliged to express somebody, namely, its composer.” This philosophy of composition as self-expression was deeply appealing to Barraine, and is arguably a major reason why so many of her works contain direct responses to the world she lived in and the issues she felt strongly about.

Elsa Barraine’s haunting Prelude and Fugue No. 2, dating from the late 1920s

She had done well at the Conservatoire, but the ultimate challenge for an ambitious young French composer was winning the Grand Prix de Rome, following in the footsteps of legends like Berlioz, Gounod, Debussy, and others. Competing for the Prix de Rome was a famously grueling challenge. After a preliminary round, the most promising candidates were sent to a final round which lasted for an entire month. Competitors were expected to compose a fully orchestrated thirty-minute cantata in the space of thirty days. The winner received the opportunity to study in Rome at the Villa Medici for a period of several years.

Barraine first tried for the prize in 1928. The attempt ended promisingly; she carried off the second Grand Prix with her Heracles at Delpes. She returned to compete the following year, when she wrote La vierge guerrière, a cantata based on the legend of Joan of Arc, and this won her the grand prize. Her victory had come at the age of nineteen, in a competition open to composers up to thirty years old. She was only the fourth woman to win it.

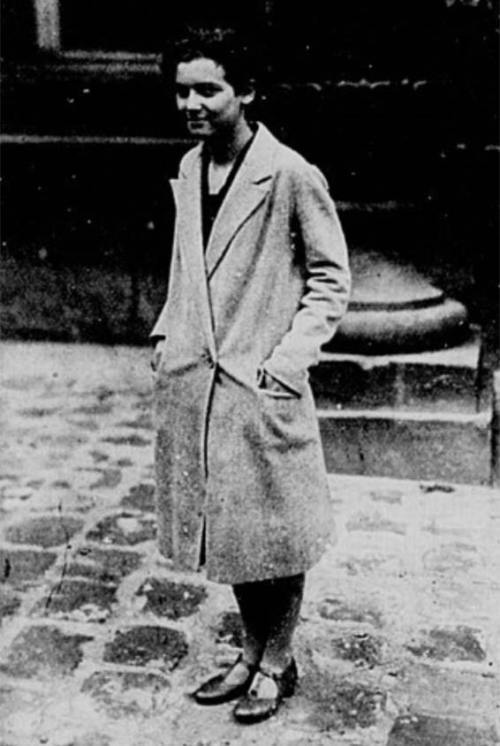

Elsa Barraine, 1929

In January 1930 Barraine and her mother made their way to the Villa Medici in Rome. It was a harrowing time to visit. Mussolini’s mission to remake and restore national greatness was seeping into every Italian’s life. Women were encouraged to abandon their careers and have babies (the state provided incentives to marry and procreate). Divorce, abortion, and contraception were banned. Children partook in military exercises. Communist newspapers were burned in the streets. Blackshirts enforced order with violence and intimidation, targeting socialists and communists in particular. (In the early 1920s, a favorite Blackshirt pastime had been pouring castor oil down enemies’ throats.) As if dealing with the culture shock of Italian fascism wasn’t stressful enough, the room Barraine was given was small and dirty. Early in her stay she wrote to Dukas that it was a “rat’s nest.”

Disgusted by her lodgings, homesick, and no doubt unnerved by the reign of Mussolini, Barraine seized every opportunity to return to Paris. But eventually she decided to use her quasi-exile to supplement her general education. She began absorbing all she could from the art and architecture surrounding her, and she read voraciously, devouring works from Norway, Russia, China, and Japan. Dukas encouraged her to study the Bhagavad Gita; entranced, she copied it out by hand. In between visiting galleries and libraries she wrote a comic opera to satisfy the sponsors of the Prix de Rome. To her relief, Le Roi bossu forced her to return to Paris for four months of rehearsals at the Opéra-Comique, where it was produced in 1932.

After three years in fascist Italy, she wrote the six minute symphonic poem Pogromes. She also brought home scores for a piano quartet, a motet for mixed choir, and a fantasy for piano and orchestra.

Barraine began her post-Prix career by teaching privately, accompanying, and choral directing. In the 1930s she secured a position as accompanist for choirs directed by French conductor Félix Raugel. In 1935 she took a job with the Orchestre national, a new ensemble specializing in radio performance. There she became their head of singing. Later, intriguingly, she took work as a sound recordist.

When war finally broke out in 1939, Barraine and the Orchestre national fled Paris for Rennes. After Rennes was bombed, the orchestra was forced to temporarily disband. When the ensemble was resurrected in Marseille in 1941, Barraine was barred from rejoining. Her ancestry and her activism had made her an undesirable employee.

Tragically she wasn’t the only one in her family to lose a job during the occupation. After a decades-long career, her 71-year-old father was pushed out of the opera orchestra. Devastated by events, he died in 1943, Nazi banners still hanging on the exterior walls of the Palais Garnier.

There was nothing left for Elsa Barraine to do but to return to Paris and try to find work as a teacher and freelance accompanist.

That and organize.

The Palais Garnier decorated with swastikas for a festival of German music, 1941. Image from Wikipedia.

In the spring of 1941, Barraine joined forces with conductor Roger Desormiere to become a founding member of the Front National des Musiciens. Desormiere resisted the Nazis in a variety of creative ways: he programmed almost exclusively French music at his concerts; he made the first complete recording of Debussy’s Pelleas et Mélisande in Paris in the spring of 1941 (a recording still revered today); he paid Milhaud’s rent when Milhaud was forced to flee the country as a Jewish refugee; and he even signed his name to Jewish composers’ work so they could continue writing during the occupation. (Desormiere ultimately unveiled their identities after the war.)

Desormiere’s enchanting recording of Pelleas et Mélisande. Elsa Barraine was this recording’s “chef de chant.”

The Front National des Musiciens eventually boasted around thirty influential members, including Dutilleux, Poulenc, and Honegger. (Honegger was ultimately suspected of collaboration and shut out.) In October 1942 the Musiciens laid out five rules describing ways in which French classical musicians could employ their art to resist Nazis. In the words of this Music and the Holocaust website:

-

Musicians were to programme concerts that would help France. Many secret concerts of Jewish composers were set up, such as those for Darius Milhaud. A public concert was arranged in Paris of a composition entitled ‘Mous-a-Rachac’ by ‘Hamid-ul-Hasarid’. The concert was a tremendous success and the Germans failed to recognise the piece as Milhaud’s Scaramouche.

-

Musicians were also to show solidarity with one another, giving half their salary to the families of imprisoned comrades or Jewish musicians in hiding.

-

Demonstrations were encouraged, such as spontaneous playing of the French national anthem La Marseillaise in the presence of German soldiers.

-

Composers were called on to provide popular songs and marches for the soldiers of the Maquis Resistance groups, using lyrics from Resistance poets.

-

Musicians were banned from collaborating with Germans, either through working on Radio-Paris, becoming involved with German concerts or festivals, or writing for German newspapers.

In addition to her leadership role, Barraine wrote for the Front’s secret newspaper, examining the use of classical music in Nazi propaganda and national identity. One of her articles was entitled ‘German music in the service of Nazi regression’; another ‘French music and the traditions of humanism.’

Unsurprisingly, Barraine’s resistance put her squarely in the Nazis’ crosshairs. Conflicting reports exist as to how many times she was arrested, but somehow, miraculously, she was always released. Nevertheless, by 1944 she found it necessary to go into hiding under the name Catherine Bonnard.

By war’s end, a full quarter of France’s Jewish population had been murdered. Even this unimaginably high proportion was one of the lowest rates of any Nazi-occupied country.

*

There is very little information available in English about Elsa Barraine’s postwar career, but it seems she retained her appetite for tackling new challenges. In addition to composing and performing, she worked as an activist, journalist (in late 1944 she became a music columnist for the Communist newspaper l’Humanité), and recordist (she became the Recording Director at the Le Chant du Monde label). In 1953 she landed a position at the Paris Conservatoire. She taught analysis and sight-reading there for nearly twenty years.

Her composing continued, too, and it boasted an extraordinary breadth. She wrote dozens of works, including Suite astrologique for chamber orchestra, music for saxophone, film music, a ballet named Claudine à l’école based on a book by Colette, variations for percussion and piano, an homage to Prokofiev for orchestra, and vocal music. As late as 1967 she was synthesizing influential trends, writing Musique rituelle for organ, gongs, and xylorimba. The work featured elements of serialism and was inspired by the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

After a long and fruitful creative life, Elsa Barraine passed away in Strasbourg on 20 March 1999. Despite the historical importance of her career, the high quality of her output, and the fearlessness she displayed throughout the Nazi occupation, her work is almost never heard today.

Elsa Barraine brought her broken world into her art, and her art into her broken world. She found music to be such a potent weapon that she risked her very life to keep wielding it. To do otherwise was, for her, unimaginable.

*

As always, a huge shout-out to the patrons who make this series of articles on forgotten musical women possible! It wouldn’t happen without you. If you want to support the series for as little as a dollar a month, click here. Entries come out every other Wednesday, unless I get steamrolled by a terrible cold, which is what happened this August. (Sorry about that.)

Here is a list of sources:

Musicologie.org article on Elsa Barraine

Historical Interplay in French Music and Culture, 1860–1960, edited by Deborah Mawer

Well, this is fascinating and depressing. She was kind of a French version of one Karl Amadeus Hartmann who, while NOT Jewish, went “underground” in his native Germany before and during the war. He composed 9 symphonies and other orchestral and chamber works. I wonder if any of Elsa’s works are on CD? Yet? Thanks very much for bringing her to our welcome eyes!

Thanks for this. Courageous musician, in more ways than one! Art to resist dictatorial regimes turns out to be quite potent. I have a friend who reminded me of the “singing revolution of the Estonians… fascinating stuff: singingrevolution.com. Your link to the prologue and fugue provided a good listen. Such a moody piece! The pipe organ is a good instrument for the piece.

A superb tribute to an amazing woman, thank you . Elsa’s 2nd symphony is a towering work; her life an inspiration.

Wow, what a story, thank you for sharing about her!

Thank you so much for writing about her! It’s a shame there isn’t a recording of La vierge guerrière on YouTube. Do you know if it’s been recorded at all?