i.

A handful of days ago, I read that the San Antonio Symphony musicians are on strike.

This is not the first time I’ve read about San Antonio Symphony drama. I actually wrote an entry about them in January of 2018. When I heard the news, I went back to read it to try to tie the thread from then to now.

J. Bruce Bugg, you may remember, was one of that near-catastrophe’s catalysts. He is a San Antonio lawyer and philanthropist who assembled a veritable dream team to remake the perpetually troubled San Antonio Symphony.

Among his compadres in the task was a lawyer named J. Tullos Wells who, according to his law firm’s website, specializes “in union avoidance and managing relationships.” Together, Bugg and Wells teamed up to create an organization called Symphonic Music for San Antonio (SMSA) to take over managing the San Antonio Symphony.

The story gets a little complicated, as everything with the San Antonio Symphony inevitably does, but if I had to choose a visual representation of how that adventure went down, this GIF from Succession sums it up pretty well.

So the SMSA collapsed. My January 2018 entry explains a little bit about why. As for Bugg and Wells, they ultimately receded from the public story being told about the symphony, and I stopped following it as closely. Last I’d heard, things weren’t necessarily looking rosy, but they seemed to be…pre-rosy. The soil had been tilled for the roses, and the fertilizer had been bought.

The reason? An indomitable woman named Kathleen Weir Vale, who became the symphony’s board chair after SMSA blew up on the launch pad. She spearheaded a fundraising drive by inviting two friends to her house, who promptly cut a check for $200,000 and triggered a domino effect of generosity. She charmed Michael Kaiser, the orchestral world’s so-called “Turnaround King”, and spoke with excitement to the press about the board hiring him as interim executive director. And she proudly told the San Antonio Woman Magazine that after the organization’s near-death experience, she went to every symphony concert for the rest of the 2018 season.

It’s important to always remember that the product is superb. Our musicians all hold advanced degrees; they are all musical geniuses. What they do for this city is unique. And I am glad that this board understands that they – the musicians – are the art. They create the art. Who wants to live in a city without music?

– Kathleen Weir Vale

By September 2018, under Vale and Kaiser’s leadership, the San Antonio Symphony ended the fiscal year $200,000 in the black.

It felt like solid ground. And it would have been, if the turnaround had been real.

It was not real.

ii.

There’s a depressing article on the San Antonio Express-News website that charts the near-annual catastrophes that the San Antonio Symphony has somehow survived. Their routine apocalypses began before I was even born.

A few choice lowlights:

1987: Musician contract negotiations fail. Rest of season is canceled.

1992: The fiscal year closes out with $4.7 million in debt. An executive director resigns.

1998: Musicians are asked for concessions. An executive director resigns.

1999: Major gifts come through. But –

2000: Deficit of $370,000. Another executive director resigns.

2002: Deficit around $1 million. Musicians offer concessions.

2003: Bankruptcy. Another executive director resigns.

February 2004: A new executive director arrives.

November 2004: That executive director departs.

2006: A beverage industry executive is appointed CEO.

2008: The beverage industry executive resigns. Jack Fishman, the former executive director of the Long Beach Symphony, becomes CEO.

2011: Despite three years of musician concessions, the orchestra ends the season $750,000 in debt.

November 28, 2012: Fishman tenders his resignation via email, effective immediately. J. Bruce Bugg does not know why he left, but surmises to the the paper, “I suspect he resigned because he had a lot of other opportunities with other organization because of his vast skills.” He also says in the same article that Fishman leaving is not a setback.

Spring 2013: A local businessman and fundraising consultant is hired as executive director.

Summer 2013: That person leaves.

September 2013: The orchestra gives up on finding a permanent CEO. Instead, they hire David Gross, the former president of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, as general manager. He is later promoted to executive director.

January 2014: A slight surplus is recorded for the 12/13 season…

June 2015: A new musicians’ contract is approved…

2016: Three-year bridge period of funding is approved by city, county, and foundation sources, contingent upon the orchestra observing “changed financial practices” to avoid deficits….

April 2017: A debt reduction plan is broached…

May 2017: The symphony board meets with donors “to discuss the state of their finances”…

July 2017: Bugg and Wells start mounting the SMSA takeover.

December 28, 2017: At almost the very last possible moment, SMSA backs out. The fate of the orchestra potentially hangs in the balance, because the collective bargaining agreement with the musicians ends on December 31.

Which brings us up to January 4, 2018, the date I posted my entry on the San Antonio Symphony. I work hard, but Kathleen Weir Vale worked much, much harder. Before that entry and over the following 48 hours following it, Kathleen Weir Vale stepped up in a really impressive way. She became chairwoman of the board, and her contacts fundraised like mad, and the orchestra survived.

For the time being.

Looking at this orchestra’s history, two things are clear, even to an uber-outsider like me.

First, this orchestra is not like the others. Obviously, something about this institution – or the fundraising context that this institution exists in – is so soul-crushingly dysfunctional that hiring a stable and competent administrative team, and getting them to stay put, has been harder than finding a nanny for the von Trapp kids. And it has been this way for an entire generation. Anyone who wants to simplify the San Antonio Symphony’s problems by suggesting fixing this is going to be as simple as scrounging up more donations is going to be sorely disappointed in the long run. They need a plan for total organizational transformation. They need to bring in their stakeholders – musicians, staff, audiences, donors, community members – and they need to chart a course that, crucially, inspires buy-in from all of them.

Second, against all odds, this orchestra refuses to die. Surely that says something, too.

iii.

One of Michael Kaiser’s nicknames in the world of performing arts is the “Turnaround King.” According to his official biography, he led the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and he erased deficits at the Royal Opera House in Liverpool, the American Ballet Theatre, and the Kansas City Ballet. He’s famous for advocating a growth-oriented mindset for large performing arts organizations. His working theory is that cuts can be dangerous, and that without continual growth, patrons and donors will lose excitement and lose interest in being a part of an organizational “family.”

On July 11, 2018, the San Antonio Symphony announced that Kaiser would serve as “interim executive director” while the hunt for a permanent CEO continued.

Kathleen Weir Vale was, understandably, over the moon about his appointment:

“It is difficult to imagine a more fortuitous event for the San Antonio Symphony at this juncture than Mr. Kaiser’s assumption of the helm. Mr. Kaiser is known worldwide as the preeminent performing arts organization turnaround specialist and as such, I am confident that he will spur our organization to unprecedented heights. A major goal is to establish systematic, disciplined, best practices in our board leadership and administrative operations. Our orchestra, our community, and all of our loyal stakeholders deserve no less. We look forward to the challenge with relish.“

– Kathleen Weir Vale

The month before, in June 2018, the orchestra had announced a new strategic plan, and the board had adopted it. “There were a whole series of specific recommendations,” Kaiser reported at the time.

What’s not part of the proposal is scaling back from a 72-member orchestra or a 30-week performance schedule in order to meet its $7.2 million annual budget.

Moreover:

“The money’s there; the money is in the community,” he said. “… This community is very generous with contributions. If you do a good job of maintaining the level of the excitement after the work and the engagement with the individual.”

The task force also recommends hiring a full-time executive director and increasing the marketing budget from 21 to 30 percent of the management budget.

Kaiser was even more explicit in an audio interview he did for the San Antonio Report in September 2018.

He was asked outright about the need for a certain number of players. His answer:

To some extent the number is arbitrary, but the truth is, what is astonishing about orchestral music is to have a group of musicians, a large number, playing in unison. And the overtones that they generate are thrilling, that you feel it. And not only do you hear your great music, but you feel this sort of wave of sound coming at you. It’s very different from what we’re used to hearing when we just use headsets. And if you start reducing that number, it becomes easy to keep reducing that number. Because “oh, we could use a few less; oh, we could do a few less violins; oh, we could do one less cello; oh, one less bass. And as you start reducing it and reducing it and reducing it, that wall of sound is no longer a wall. And it’s not that it’s not wonderful to hear a string quartet. But you don’t want to hear a string quartet play a Beethoven symphony. And so we need to protect the size of our orchestras even though it’s financially challenging. Because we don’t want to cheapen the product.

Kaiser was also asked if he thought that enough financial support existed in San Antonio to support not just the day-to-day operations of the orchestra, but an eventual endowment drive, as well. Kaiser said yes. This was the road map he sketched out:

It absolutely is a realistic possibility! We just have to do it in a smart way. We already have about two million dollars that are not technically an endowment; they sit in a donor-advised funds, but we benefit from the income of those in perpetuity. So there is a part of a structure already in place. We definitely want an endowment; we definitely need an endowment. But an endowment drive comes after an organization feels extremely solid and the donors say this is going so well, now we want to make that very large gift that’s going to make sure this continues in the future. There’s no questioning that this institution has had some rocky years behind it. And we need to convince a group of major donors that we’re here to stay, things are on the upswing, and frankly I think that’s going to take the appointment of my replacement, of a permanent executive director, but when we do, and when we’ve gone through another year or so and people go, wow, this is really on a great trajectory, that’s when it’s possible to go for those very large gifts. Until that point in time, I think we have to focus on getting the annual gift in, making sure we are balancing our budgets, and making sure that we’re looking rock solid.

So of course the next question was, what qualities would the next executive director need to possess?

I always refer to this job as an arts entrepreneur. Someone who builds connections. Who finds ways to build audiences, who finds ways to build connections to new donors, who finds ways to build connections to other arts organizations or educational institutions or other kinds of institutions, and build these relationships that increase the size of the institutional family. I think that’s an entrepreneurial function. And so it’s gotta be someone I think who knows how to do this in an arts environment. I think one thing many arts organizations have suffered from is hiring often as an executive director someone without that expertise. They’ve been successful running something but not necessarily an arts organization. And it doesn’t mean they aren’t wonderful managers. But there are tricks to the trade and there are things to know about running an arts organization. And I hope that anyone who comes in has that rock solid knowledge and entrepreneurial zeal to go out and make connections throughout the whole San Antonio community and potentially beyond.

In September 2018, the San Antonio Symphony, under the leadership of Michael Kaiser and Kathleen Weir Vale, announced it had ended its season $200,000 in the black.

iv.

Michael Kaiser expressed certainty in his September 2018 podcast interview that some great permanent executive director candidates would emerge for the San Antonio position.

“When you’re approached by an organization that already has shown there’s a group of people who are truly passionate, who are really willing to work hard and show results and in a city where there’s so much growth and potential, that to me was extremely exciting, and I believe it will be exciting to many people who will be interested in having a permanent executive director position here at the San Antonio Symphony.”

The winner of the search was announced on November 13, 2018. His name was Corey Cowart. He had been the executive director at the Amarillo Symphony since 2015, and before that, he was on the administrative staff of the Minnesota Opera and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. He plays the trombone.

In March 2019, once he’d gotten settled, he did a joint interview with Vale for the San Antonio Report. Vale raved, “He’s an American orchestra professional executive director, who comes to us experienced, seasoned. Other people have learned on the job, but he’s got all the chops. We don’t have to wait for him to learn. He’s teaching us. He’s teaching us what to do, how to do it.”

Now is where I’m going to get nitpicky. Especially given later events, there were several moments in the interview that struck me as odd, or even alarming.

RR: A month ago, Kathleen, you said Corey has some proven strategies for marketing, so you decided not to hire a new marketing director yet.

Cowart: The most important thing we have to do is grow our audience and grow our subscription base. When you look at how critical that is, we can’t afford to get it wrong in how we execute or the things we choose to do. … We engaged a firm – CR Stager [based in New York] – to basically be our interim director of marketing, to hit the ground running as we work to build and train our staff in that capacity. They’re basically the industry experts in orchestral marketing. … We’re focused on the absolute fundamentals, and they’re the right team right now to help lead that and also to help as we bring on more staff, to coach our staff in best practices, and how to execute.

RR: And what are a couple of those key fundamentals?

Cowart: Primarily it’s direct mail, it’s radio, newsprint, and telling people what’s actually being played.

The other thing is just getting into more radio advertising in a way that’s focused on helping people along with what the concert sounds like. As an example, not everybody may know what every Beethoven Symphony sounds like. But there’s a reason [Symphonies No.] 3, 5, 7, and 9 sell a lot better than the others. So if you help out, even with just those opening bars of Symphony No. 2, everybody’s heard that before, and it’s like, “Oh yeah, I can come to that.” So just those basic things.

RR: Where is this orchestra in five years?

Cowart: I’m not going to be egotistical enough to say I have an answer for that. It’s a question that we need to all figure out together. Being here only a little over two months, we’re still trying to figure out exactly what those questions are, but that’s with the musicians, with the board, with the other community stakeholders.

For me, at a high level, it’s that we are seen as an artistically ambitious and financially strong cultural leader for our region, whatever that needs to look like. But drilling down on the specifics of that, that’s where we need a whole lot more smart people than me in the room and talking about it.

Look, to be clear, I totally support listening to the community and taking their wishes into account, but…surely the leader of a big orchestra should be able to communicate a more compelling answer to this question than, basically, “I’ll get back to you.”

When Vale was asked the same question, she had a much more dynamic answer. (Albeit one that did not age well.)

RR: Kathleen, what does the Symphony look like in five years?

Vale: … It’s a place where the hall is filled when we perform. It’s a place where the musicians are thinking of as a destination orchestra. We have many, many musicians for whom it is a destination – very fine, world-class musicians. They’re geniuses, they’re wonderful musicians, gifted, dedicated, devoted to the city, devoted to their families, their community, their students, their audience, and my vision is to have them in a situation where they’re financially secure, where they wouldn’t dream of leaving SA.

RR: Is it a full-year performance schedule for them at that point, versus the current 30-week schedule?

Vale: I think it probably could be expanded, yes, it could be grown. They would love that. Those musicians live to play, they live to make art. They are the art, and they make the art.

v.

Almost a year to the day of that joint interview, the world fell apart. Suddenly, with the advent of the pandemic, orchestras all around the country were forced to swim for their lives. The San Antonio Symphony was no exception. Their musicians gave back a big chunk of their compensation to help keep the ship afloat.

That said, despite the difficulties, as recently as May 2021, executive director Corey Cowart seemed optimistic about the future.

We were very fortunate to be reenergized by the recruiting of the board of directors who really stepped up in their engagement, philanthropic support, and the overall health of the organization (after the management change). Coming out of that, there was momentum being built and that’s right when COVID hit. Just like every other arts organization in San Antonio and internationally, that impacted us with millions of dollars of challenges. From concerts that weren’t happening and funding institutions that, rightfully so, were switching focus to food banks and the things that are critical need when so much of our society is hurting. We’ve had to drastically reduce our budget this year—it is less than half of what it has been historically. But we’ve been fortunate. I think 85 percent of our patrons that had purchased tickets to the cancelled concerts in 2020 chose to donate the value of the tickets back to the symphony. It’s been challenging, but we’ve been able to navigate through with announcing this next season and being back to live concerts. We are trying to get this momentum to really do the best we can to capitalize on the huge amount of pent-up demand for just doing things again and in a safe way.

– Corey Cowart

On September 13, the management team made a “last, best, and final” offer to the San Antonio Symphony musicians. Management might as well have told Michael Kaiser to go to his car, burn his car, and then take the bus and go home.

The San Antonio Reporter reported on September 27:

On Sunday evening, San Antonio Symphony management declared an impasse in negotiations in order to impose contract terms that would mean a reduction from 72 full-time positions (71 musicians and one music librarian) to 42, with 26 part-time musicians to bring the full complement of the orchestra to 68 members…

The musicians’ negotiating committee rejected the notion of becoming a “split” orchestra of part-time and full-time musicians. They also said no to an earlier offer of a nearly 50% pay cut and a subsequent offer of a one-third reduction in pay and health benefits for full-time musicians, and proposed yearly wages of $11,250 for part-time musicians with no health benefits.

This during a pandemic. In Texas.

Vale is quoted in the article as saying, “It’s very difficult for all, for the board, for the organization, it’s difficult for everyone. We love our musicians, we love our orchestra, we love our art. And it’s very difficult. I can’t imagine a board that loves its artists any more than this one.”

So obviously there are a lot of questions here.

What happened to Kathleen Weir Vale? Why exactly did the tenor of her statements change so utterly? (I don’t know.)

What happened to the board-approved ideological road map from Kaiser, a leader whose ideas she once embraced so wholeheartedly? (I don’t know.)

Was Kaiser wrong when he said it would be possible to fundraise for an endowment in San Antonio? (I don’t know.)

Why does nobody in this situation on the management side seem to understand that they are about to drive away many musicians, who will make more money doing pretty much anything else? (I don’t know.)

Why are they so convinced they’ll be able to get more money from a community by presenting a smaller-scale product? Have they done the extensive market studies on how their audience will react? Surely they did. Didn’t they? Didn’t they? (I don’t know.)

Why are they pursuing a permanent solution to what appears to be, by their own public statements, a situation caused primarily by Covid? Because Vale was talking about expanding the season the year before the pandemic started. Or was the “momentum” post-Kaiser all a mirage? (I don’t know.)

What is happening? (I don’t know.)

Do I have the answers? F*ck, no.

As this thing drags out, more answers may come out, and they may define their position more clearly. Until then, I feel like we’re left to guess about a lot of things.

But one thing seems clear.

If the citizens of San Antonio want to preserve a chance at rebuilding their orchestra, they – rich and poor alike – are going to have to team up and figure out yet another way for the orchestra to cheat death (again). This revolving door of leadership has got to stop spinning. The toxicity has to be addressed, and the bizarre ideological zigzagging surrounding the last few years resolved and explained. Because so many people want the music to go on. They need and deserve that now more than ever. That’s something that hopefully everyone can agree on.

epilogue

Might J. Bruce Bugg have some role to play here, you ask?

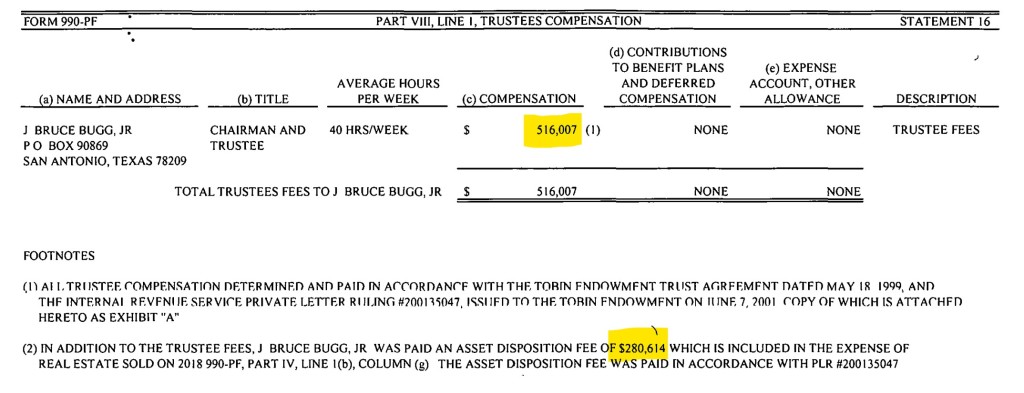

Probably not. Or if he wants to, you probably want to gently dissuade him from getting involved. The other day I looked at the most recently available Tobin Endowment 990, which is for fiscal year 2018. Bugg paid himself $516,007 in trustee fees. He still claimed he spent forty hours a week working on the Tobin Endowment, despite the fact he also had several other jobs at the time, including Chairman of the Texas Transportation Commission. In addition, he was paid an asset distribution fee of $280,614 for the sale of property. So according to the 990, he walked away from the Tobin Endowment with just shy of $800,000 in compensation that year alone.

In February, he was reappointed by Governor Abbott to the Texas Transportation Commission. As one last endnote for this entry, he has gone into the coronavirus testing business, cofounding an organization called Community Labs. His partner in the venture is his buddy from SMSA, Tullos Wells. Community Labs is, like the Tobin Endowment, a non-profit.