Here is a long article entitled “Women Violinists of the Victorian Era” from the February or March 1899 edition of The Lady’s Realm, a British magazine. The author is unknown. Original here.

***

Before the days of Paganini, and even as far back as the middle of the last century, a girl-violinist appeared now and then upon the concert platforms of Europe. Yet it may be asserted, without misgiving, that all celebrated lady-violinists are of the Victorian Era.

The first women who attained enduring fame as violinists were the sisters Milanollo, the outlines of whose artistic careers have often enough been sketched, though unfortunately not always with accuracy. But the ever-gracious Teresa Milanollo (now Madame Parmentier) has kindly placed at my disposal the fullest details concerning her public life, and has courteously permitted the readers of THE LADY’S REALM to be told more than is usually known of her personal history.

Born at Savigliano (Piedmont), August 28th, 1827, Madame Parmentier is now in her seventy-first year. But the disposition of Teresa Milanollo is still young and fresh, her interest in things musical, and zeal for philanthropic service, as keen as ever.

The vocation of this great artist manifested itself in very early days. At four years of age she was taken to a funeral ceremony in honour of King Charles Félix of Sardinia, and upon leaving the church her father put to her the question: “Did you pray to God, little one?” “No, papa,” was the reply, “I did nothing but listen to the violin.” After this she was persistent in her demands for a violin of her own. Her father instructed her in the elements of solfeggi, and then made for her a little violin in white wood, and put her, for a year, under the tuition of Ferrero at Savigliano. Later on she had lessons at Turin from Caldera and from Morra, but not of Gebhard, as has been often stated.

She was only in her ninth year when she made her début and appeared at several concerts in the vicinity of her native town. In the year 1836 she was taken to France, to play at the Musard Concerts at Marseilles. There she had an immediate success, and went on to Paris, where she had some lessons from Lafont and played once or twice at the Opéra Comique. The same year she went with Lafont for a tour in Belgium and Holland, and in 1837 played at Amsterdam and the Hague. In this year too – the year of the Queen’s accession – she came to London, and was heard at Covent Garden.

In London she took some lessons with Mori and Tolbecque, and was engaged by the harpist Bochsa to make a three months’ tour in Wales.

It was upon her return to France, in 1838, that her little sister Maria, then six years old, was first presented to the public. Soon after this, Teresa put herself under the musical direction of Hebeneck, who made her play his Grand Polonaise in C, at one of the celebrated Conservatoire concerts, April 18th, 1841. In the opinion of all the critics of that time, and notably of Berlioz, her success was immense, and it was this appearance that definitely crowned her reputation.

The same year, the sisters Milanollo played before Louis-Philippe at Neuilly, and from this period, they were inseparable until the death of Maria. The younger sister never received any lessons except those given her by Teresa. About this time the sisters met de Beriot, who communicated to Teresa the masterly bowing of the school of Viotti and de Baillot, and the faultless intonation which so many, even illustrious, performers lack. To de Beriot Madame Parmentier accords the distinction of having “completed her artistic education.”

From this time (1842) forward until 1848, when the melancholy event of Maria’s death from rapid consumption occurred, the sisters were continuously journeying through Europe. In every capital, and in most towns of importance, they appeared at series of concerts; their reputation increasing each year. In Vienna, particularly, the honours of public favour were heaped upon them. They appeared with Liszt at the Castle at Brühl before the King of Prussia, and in Berlin the furore they created had, according to the cirtic Kellstab, been equalled only three times in the century. The three performers whose successes he ranked with theirs were Catalini (the prima donna), Paganini, and Liszt. While in Berlin the sisters twice played before the Court, accompanied by the composer Meyerbeer.

In 1845 they paid their second and last visit to London, where they gave several concerts, and played before Her Majesty at Court.

It is a strange thing that at a time when the music-lovers of the Continent were all wildly enthusiastic for the sisters Milanollo, and their popularity abroad supreme, the English public gave them a comparatively lukewarm reception. But in 1845 England had scarcely earned the reputation of a music-, or rather virtuosi-loving nation. The days of Sarasate- and Paderewski fever had not yet dawned in Britain, and the really musical among us could be counted only by hundreds, instead of, as now, by many thousands.

The terrible sorrow into which Teresa fell, upon the loss in 1848 of her much-cherished sister and pupil, was stupefying in its intensity. But her father, who had recently bought a country estate at Malzéville, near Nancy, urged upon her the wisdom of reappearing in public. She played, therefore, at a concert in aid of the Association des Artistes Musiciens, gave two quartet concerts in Paris, and subsequently toured in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

Her last professional concert was given on April 6th, 1857, at Nancy, and on the 15th of the same month she married General (then Captain) Théodore Parmentier. At the time of their marriage, General Parmentier was aide-de-camp to General Niel, with whom he took part in the siege of Sebastopol. Since her marriage, Teresa Milanollo’s appearances in public have been comparatively few, and all have been at the call of charity.

Many are the charming stories told of the ceaseless benevolence of Teresa Milanollo. During the lifetime of Maria, the sisters had already put themselves into direct personal relations with the poor of Lyons; but it was after Teresa had roused herself from her mourning that she invented the system of “Concerts aux Pauvres,” which she carried out in nearly all the chief towns of France. At these concerts she reserved part of her receipts for the benefit of the poor. Then in each town she appeared again before an audience composed exclusively of the children of the public schools and their parents. To these she played in a manner which strangely silenced and moved her hearers, and at the conclusion of her performances, money, food, and clothes, the products of her self-charged receipts from the previous concerts, were distributed.

From 1857 to 1878 she, a soldier’s wife, followed the fortunes of her husband, and one of her later appearances was at a concert at Constantine, Algiers. Since 1878 the gallant General who is “Grand Officier de la Légion d’Honneur,” and his gifted and famous wife, have resided quietly in Paris; but, generous and accessible as ever, Madame Parmentier is still to be met by a fortunate few in select musical and social circles of the French capital.

Teresa Milanollo is not alone distinguished as the first really famous lady-violinist, she is also remembered for being the most pathetic and soul-moving performer of modern times. All her effects were obtained by legitimate means. Maria’s distinction rested on other grounds. Without pretending to the grand style and electric emotion of Teresa, she had remarkable vigour and boldness of execution, and her staccato was so perfect that she received, in Germany, the nickname of Madamoiselle Staccato, in opposition to her sister, who was dubbed Mademoiselle Adagio.

To Brussels, the cradle, then and now, of so much musical talent, belongs the honour of having given to the world, in the early ‘fifties, some excellent lady-performers on the violin. Among them was a Mademoiselle Fréry, a favourite pupil of Charles de Beriot. Dr. T. L. Philson, who was present in the great concert-hall of the Grande Harmonic when Mademoiselle Fréry competed for the first violin-prize of the Brussels Conservatoire, states that she was not only a fine player, whose performance on that, as on subsequent occasions, was greeted with storms of applause, but a very beautiful girl. He recalls her, with black, flashing eyes and dark hair, sitting behind the stage with her mother, fingering her violin in an agony of nervousness, though apparently calm, until it should be her turn to appear before the judges. When the moment came, to the surprise of every one, her courage failed her. She refused to go forward. Nor could her bashfulness be overcome until de Beriot himself, leaving the conductor’s desk, went to her and led her in her little white frock and pink sash, blushing and trembling, before the audience. The chief merits of this player were her “full, luscious tone,” and refined expression. Like many another talented beauty she was married early (to a pianist, with whom she went to the United States), and disappeared from European musical circles.

Not long after her successes, Brussels – in 1853-4 – hailed with the enthusiasm the début, at the Opera House, of the Demoiselles Ferny, who were pupils of Artot. These two sisters speedily became popular favourites; and the similitude of their name – Ferny – with Fréry, undoubtedly completed the extinction of the earlier star, who deserved to shine a little longer in the recollection of music-lovers.

After Teresa Milanollo, the next name to stamp itself indelibly upon the public consciousness is that of “Norman-Neruda.” Other women-violinists, notwithstanding great talents and sensational successes, scarcely attained to the true immortality of fame. But the position of Neruda, in the hierarchy of musicians, is one that cannot easily be overthrown.

Wilhelmina Neruda, born in 1840 at Brünn in Moravia, began to play the violin almost as soon as she could walk, and appeared in public at Vienna in 1846. Her master was Jansa. At nine years old she played a concerto of de Beriot’s at the London Philharmonic Concert, and was enthusiastically received. In 1865 she married Ludwig Norman, a Swedish musician, and five years afterwards played again at the Philharmonic, and was induced by Vieuxtemps to remain in London until the winter, when she accepted the post of leader of the quartet at the Popular Concerts. From that time it has been the good fortune of Londoners to hear her every winter at St. James’s Hall.

Of her perfect education, refined and intelligent phrasing, and depth of feeling, it is unnecessary to speak. The violin she uses is the “Strad” that belonged to Ernst; it was presented to her by the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and a few other distinguished amateurs.

Upon the death of Ludwig Norman, Madame Neruda married Sir Charles Hallé, with whom she made a most successful tour in Australia. In 1895, as none of us have forgotten, Sir Charles Hallé died, and, upon the suggestion of the Princess of Wales (of whom “Neruda” has long been a personal as well as a musical favourite), a subscription was raised for his widow. In 1896 Lady Hallé was presented by many admirers with the title-deeds of an estate and villa in Italy, and a purse of £500.

For so long now Lady Hallé has been a favourite of the British Public, for so long she has resided in our midst, that it is difficult to think of her as other than an Englishwoman. Yet neither her birth nor her parentage gives us the right to claim her as our own. But there is something in the repose and “at-homeness” of Lady Hallé’s bearing, both in public and private, and much in her devotion and loyalty to the British audiences who have delighted to applaud her through nearly half a century, that warrants the pride we all feel in our lion’s share of possession of her personality and talents. More than any other of the great violinists of the Victorian Era, she belongs to us. England may be proud of being the country of this great artist’s adoption. Her Majesty’s recognition of her husband, and the English title which, through him, “Norman-Neruda” bears, only serve to emphasize our claim to count her one of us.

Gabrielle Wietrowetz was born at Graz in Styria, in 1866. She is the daughter of an orchestral musician, who taught her all he could until she was placed in the Styrian Musical Society’s School under Caspar. Aided by the Styrian Government, Fräulein Wietrowetz entered the far-famed Hochschule in Berlin, where she worked under Joachim. Twice she won the Mendelssohn prize, and, at eighteen years of age, appeared at the Berlin Philharmonic Concert, when she played Max Bruch’s second concerto.

After playing in Bremen and other German towns, she came to London, and, among other engagements, has been heard several times as leader of the “Pop” Quartet. The breadth of her tone and beauty of her phrasing are remarkable; her interpretation of the music of Brahms being particularly striking. A woman of great strength and determination, she puts it all into her playing, adding much charm and tenderness.

Teresina Tua was born in 1867, and first appeared as a prodigy in Nice when seven years old. After a successful concert, she attracted the notice of a wealthy Russian, Madame Rosen, through whose interest she became pupil of Massart at the Paris Conservatoire. Queen Isabella of Spain, and Madame MacMahon (wife of the Field-Marshal) were also among those whose early notice contributed to the fostering of “La Tua’s” remarkable gifts. She appeared for the first time in England in 1883, when she created much sensation at the Crystal Palace Concerts, and played with success at the Philharmonic. She has visited America, and appeared in most of the chief cities of Europe. Upon her marriage with the Comte de Franchi Verney della Valetta, she retired for a time from public life, but re-appeared in Italy in 1891. In the January of last year she was heard once more in England, and gave a well-attended recital at St. James’s Hall. It is generally agreed that her style is now more matured; some earlier eccentricities having quite disappeared. Her tone is small, but the refinement of her expression and phrasing are delightful. She is, in every sense of the word, a charming player.

Irma Sethe, one of the most remarkable of living violinists, was born at Brussels in 1876. When only five years old she showed exceptional talent, and her mother persuaded the celebrated violinist, Jokisch, to give the little one lessons on the violin. After three months’ study she was able to play a sonata of Mozart’s, and at ten years of age she played a concerto by de Beriot, and a rondo capriccioso by Saint-Saëns, at a charity concert, when she was received with much applause.

Irma Sethe, one of the most remarkable of living violinists, was born at Brussels in 1876. When only five years old she showed exceptional talent, and her mother persuaded the celebrated violinist, Jokisch, to give the little one lessons on the violin. After three months’ study she was able to play a sonata of Mozart’s, and at ten years of age she played a concerto by de Beriot, and a rondo capriccioso by Saint-Saëns, at a charity concert, when she was received with much applause.

The following year she made a still greater success at Aix-la-Chapelle, with the result that many engagements poured in upon her. But her mother wisely refused to allow her to begin her public career so early. She continued under the tuition of Jokisch until her fourteenth year, but spent her holidays in Germany, where she had lessons from Wilhelmj, who gave her a violin. She studied subsequently under Ysaye, who, surprised at her talent, advised her to enter the Brussels Conservatoire. After studying there eight months, she won the first prize. She was then only fifteen. In 1896 she appeared in London, and, during the Jubilee season, gave an orchestral concert at the Queen’s Hall.

Her playing is remarkable for great breadth of town, for refinement, combined with almost masculine power and intellect, and for an absolutely perfect intonation. In the opinion of many musicians, she is the finest lady-violinist who has yet appeared.

It is fortunate for the music-loving public that Irma Sethe’s marriage, which took place in Brussels last August, has not withdrawn her from the concert-room. With her husband, Dr. Saenger (littérateur and Professor of Philosophy at Berlin) Madame Sethe-Saenger has made her home in a charming modern flat in the Prussian capital. And as much as she delights in her Art, there is ever a wrench when she tears herself away from the calm and luxury of home, to fulfil the numerous engagements which are made for her by her agent Cavour in different parts of the Continent and British Isles. Her recent autumn visit to this country, when she played in the more important of our provincial towns, re-visited Scotland, and made her first appearance in Ireland, proved to her numerous admirers that hand and soul have not lost their cunning, nor wifehood staled the marvellous artistic power of Irma Sethe-Saenger.

Of English lady-violinists of the present reign, the earliest perhaps to commend herself to critical favour was Miss Browning (now Mrs. Osborne Ince) whose name is almost forgotten, though she is still living in our midst, and in touch with London musical life. This player had a breadth of tone which, in days of too exclusive devotion to technique, is refreshing to recall.

It was in 1874, in her very youthful days, that Miss Emily Shinner went to Berlin to study the violin. At that time – it is hardly credible in our more enlightened days – female violinists were not admitted to the Hochschule, so Miss Shinner had to content herself with taking private lessons from Herr Jacobsen. But one morning she was suddenly made aware of the fact that a lady-student who, in ignorance of the rules, had travelled all the way from Silesia, was, through the kindness of Professor Jachim, about to be examined for admission to the Hochschule. The English student lost no time in presenting herself as a second candidate. The result of the examination of both ladies was their acceptance of probationers, and they became thus the first two lady-students for the violin admitted to the famous Berlin Academy. At the end of six months, Joachim heard Miss Shinner play, and decided to take her as a pupil, whereby she gained the further distinction of being the first girl-violinist to study for the profession under the great master of our day.

About fifteen years ago, Miss Shinner was called upon, at short notice, to take Madame Neruda’s place as leader of the “Pop” Quartet. It appears to have been Miss Shinner’s destiny to break new ground, for she was the first lady to receive the honour of appearing in Neruda’s accustomed seat at the Popular Concerts. The middle movement of the quartet was encored; but so inexperienced was the young leader that it was only upon the hint of Mr. Ries that she accepted the encore and began it again. Since that time, Miss Shinner has always been more or less before the English public, and has devoted herself particularly to chamber music and quartet playing. Only two years ago she played Bach’s double concerto in conjunction with Joachim at the Crystal Palace. Her marriage, with Captain A. F. Liddell, took place in 1889.

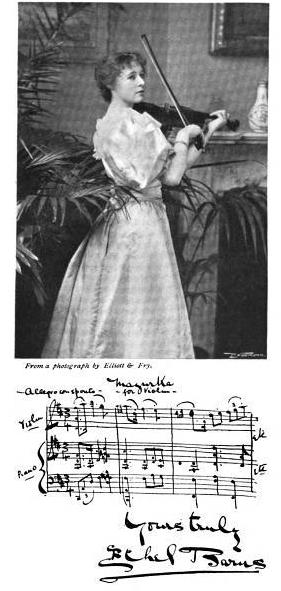

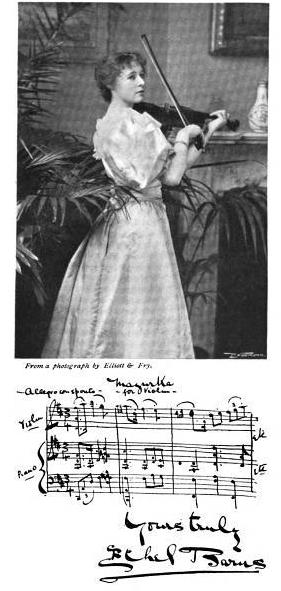

Miss Ethel Barns is known both as a performer and as the composer of some charming violin solos. If there be anything in graphology, one ought to read some exceptional characteristics – an infinite power of taking pains, a precision, a force – in her musical hand-writing, characteristics which are all invaluable to a violin-player.

Another English violinist, just now coming to the front, is Miss Jessie Grimson. She was trained by her father, Mr. S. Dean Grimson, until 1889, when she won a scholarship at the Royal College.

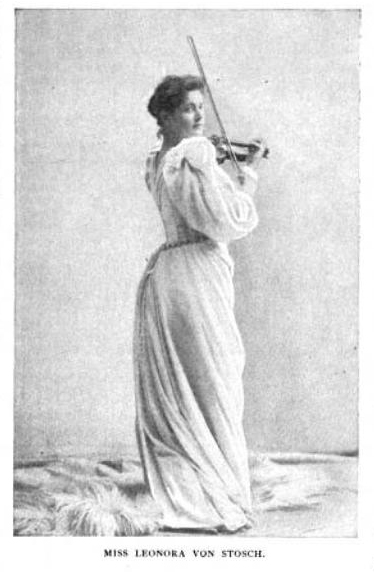

Among a crowd of stars, whose persistent shining reveals them at last to sight, one appears sometimes with sudden meteor-flash. Miss Leonora Jackson is one of these.

Madame Soldat is a French player of exceptional ability, and the leader of the Viennese Ladies’ Quartet.

Among other lady-violinists who have become known to English audiences during the Victorian Era are Bertha Brousil, who now devotes herself to teaching; Terese Liebe, once resident in London, but at present living abroad; Marrie Motto; Nettie Carpenter; Anna Lang; Frida Scotta, who has appeared in most of the continent capitals, including Moscow in 1896; Marianne Eissler; Beatrice Langley; Louise Nanney; Camilla Urso; Edith Robinson.

We, of this time, have outlived the dark ages when the violin was looked upon as an exclusively manly instrument. It is one of the surest marks of progress in the Victorian Era that those days are passed. The fame of a Paganini, of an Ernst, of a Joachim, of a Sarasate, is a fame which women have proved themselves full worthy to share.