The year is 2012. The place is the Danish Music Academy concert hall in Copenhagen. The event is the Wunderground Festival. On the program is a work called Svævninger (or Beats).

Before the performance begins, an elderly woman wearing a prim white blouse and a long black skirt descends several steps onto the stage. She is a composer named Else Marie Pade. She is 88 years old and has composed for decades, but she has never heard her work performed in front of a live audience before. Svævninger has been a collaboration with Danish sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard, a colleague half a century her junior.

The two walk slowly across the stage, arm in arm. They acknowledge the audience, then take their seats behind a laptop and a mixer.

“Are you ready?” Kirkegaard asks quietly.

She nods.

The auditorium lights dim to blue. Otherworldly sounds start seeping through the space: eerie, disorienting pulses, a magnetic hallucination.

“That’s good,” she murmurs.

“Yes.”

She looks up to the ceiling where the sky would be.

Documentary by Sofie Tønsberg about the performance of Svævninger

*

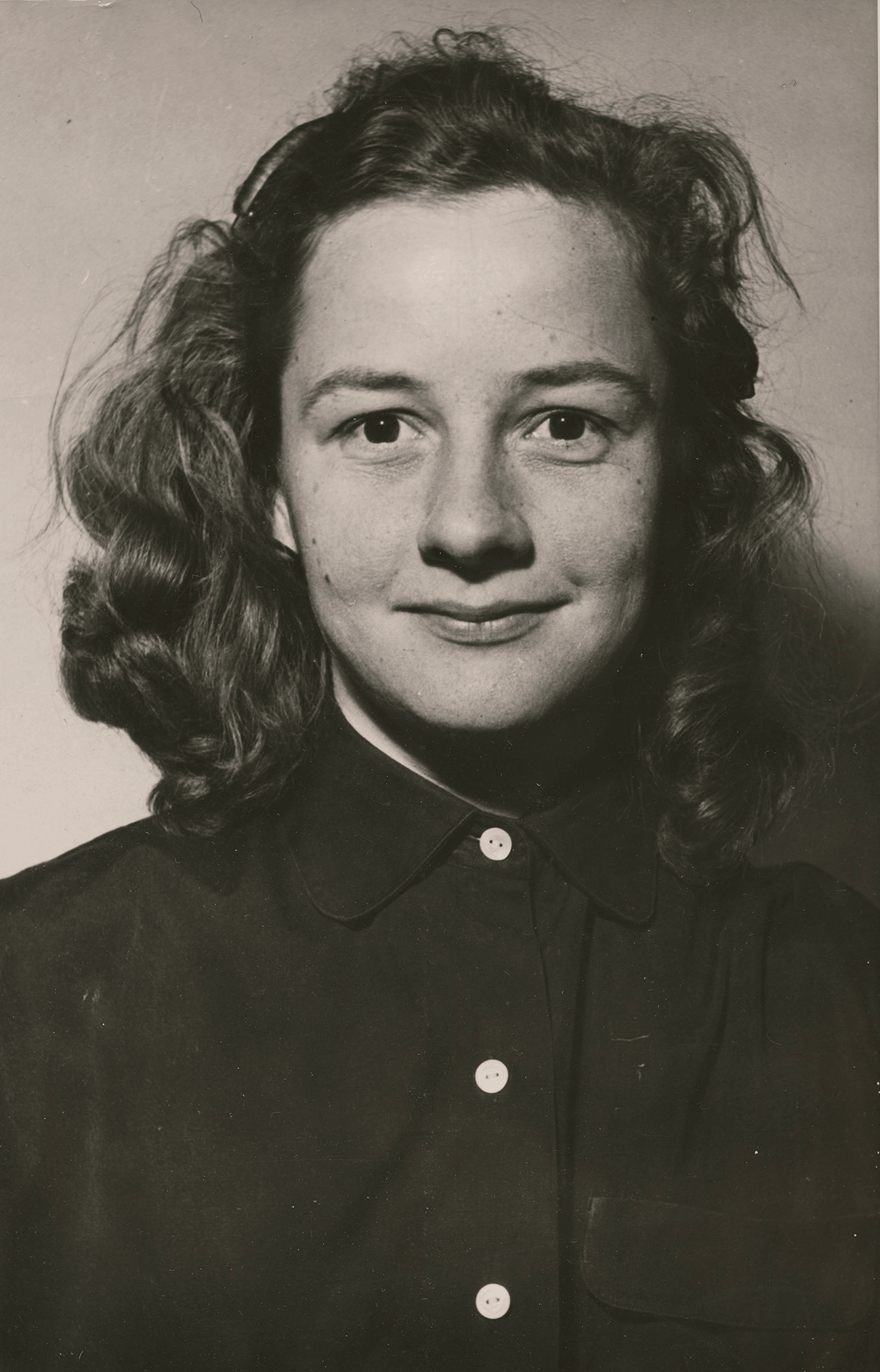

Else Marie Pade was born Else Marie Jensen on 2 December 1924 in Aarhus, Denmark. Soon after her birth she was diagnosed with a recurring kidney infection. As a result she spent countless months bedbound, motionless, just listening.

An older sister had died young, and her parents were frantic to protect and nurture their surviving daughter. One day, hoping to make temperature-taking easier, Mrs. Jensen began to sing. Else Marie was transfixed. Then, out of curiosity, she switched to a minor key. This made Else Marie cry. The experiment was run several times. The results were always consistent.

“A friendly fairy had given me as a gift in the cradle the ability to be receptive to the world of sound,” Else Marie wrote in 2004.

Mrs. Jensen instilled in her daughter a love of all the arts: literature, opera, theater, film. She also began teaching Else Marie piano (although the little girl rebelled against the necessity of scales).

Her father, on the other hand, promoted games and logic puzzles, fascinations that would later manifest themselves in her creative life. “He turned up with jigsaw puzzles, mosaic games, card games, alphabet blocks, number lotteries. He played, taught me the rules, acted as my playmate.”

But her parents couldn’t provide constant companionship. So she spent endless hours alone, taking refuge in her imagination, reading fairy tales, listening to the radio, or simply noticing the sounds that she heard coming from the street. She saw in the forced inertia of her illness a key to a secret creative world.

In a sense this minimalistic world I was in contained just as many sensory impressions as the spectacular world in which the busy, active people moved. It was like being a drop in the ocean. From morning to evening there was life and sound around me. The day started for me with morning sounds – sponges with splashing and dripping in the washstand; the kettle whistling; the birds, also whistling if the rain wasn’t pouring down; different footsteps, friendly words – and temperature-taking songs.

The days passed with reading aloud and toys when the worst of the fever was over; and the radio played for me and read to me and explained things. When the window was opened, I could hear carpet-beating, the caretaker sweeping the yard and the children playing. Sometimes I came into the living room for a while and sat on the sofa. There were quite different sounds there: heavy horses’ hooves on the paving stones, horses and carts that arrived with bread from the baker opposite – horses for this and horses for that – and bicycle bells. There was a confusion of sounds – the street vendors’ cries and much else.

I learned very quickly that some of the sounds came at a particular time of the day in a particular order – every day. I also learned that during the day the sun could make the birds sing, while the moon could not make the stars say anything, although it looked as though they would like to. They twinkled. All that could be heard at night was bird calls and the moaning of the wind, cats miaowing and the sirens of ambulances now and then. So then I decided to give the stars some sounds of their own. I formed tiny little tingly sounds with my lips, and the Man In The Moon, whom I firmly thought I could see, laughed back at me – a deep, friendly laughter.

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

Her love of sound and music led her mother to sign her up for piano lessons outside the home. She ultimately received financial aid to attend the folk music school in Aarhus.

As she got older, her health improved and she began exploring new creative horizons. When she was a teenager, she borrowed a portable record player and heard New Orleans jazz for the first time. She instantly fell in love with the genre, and soon she started a jazz band of her own called The Blue Star Band, which played at school events and youth associations.

In those years I discovered that behind the apparently wild, wanton jazz and the popular schlagers (the Top Ten of the time) there was a set of rules as strict as in Beethoven’s sonata forms. I had always loved fantasizing for myself on the piano; now I began to compose – schlagers – and to improvise on jazz themes. My parents despaired.

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

Her family discouraged her from delving deeper into the world of popular music, despite the joy it brought her. But it proved to be a passion she couldn’t shake. Behind her parents’ backs, in order to prepare for further musical education, she began taking piano lessons with a woman named Karen Brieg, who taught at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Aarhus. “Karen became the best friend and confidante I had in my life, which turned out to set my life on a different track from the one I was following before,” Else Marie explained in 2004.

*

The life of every European was put on a different track once World War II broke out. In April 1940 the Nazis invaded Denmark. Else Marie was only fifteen, but even then she found the scourge of fascism abhorrent. The Nazis’ behavior reminded her of the cruel oppressive kings that she’d read about in her treasured fairy tales.

[The invasion] gave rise to a righteous indignation in me that went beyond all bounds. I considered it incredibly cowardly that a giant country occupied a tiny little country that had done no one any harm. They called themselves the German Wehrmacht (defence forces), but behaved as the German master race. I protested!

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

Despite the risks to her safety, she joined the Dansk Samling (the Danish Unity Party) and began distributing underground publications to promote their cause. One day she even went so far as to spit at at a column of German soldiers marching through her hometown. She was chased and almost caught, but somehow she escaped, eventually turning up at her piano teacher Karen Brieg’s home.

Brieg was furious. According to Else Marie, she said, “Stop that sort of nonsense! You’re putting both your own and others’ lives at risk. If you want to do something, it has to be done properly.”

“Well, then, I’d like to,” Else Marie replied. “But where can I go to do it?”

And with that question, a whole new world opened up to her. Brieg revealed that she was the leader of an all-woman Danish Resistance group, and that Else Marie was welcome to join. Accordingly, she ramped up her activism in 1943, the year she turned nineteen. That August she began delivering illegal newspapers. By 1944 she was learning how to use weapons and explosives. There was a plan to blow up the Germans’ phone lines to assist in the event of an Allied invasion.

Her circle of friends used their outwardly flighty femininity to throw the Nazis off their tracks. They’d giggle in groups together, pretending their socks had fallen down, then kneel and fix them while scoping out various strategically important locations.

“Usually it went really well,” she remembered decades later. “But we were shadowed all the time and then one morning there were knocks on all our doors. They caught the whole group and put us into Frøslev prison camp. We knew very well what we had been doing. But it was not fun for the parents, because they did not know anything. Oh, it was ugly.”

Else Marie was arrested by the Gestapo on 13 September 1944, a few months before her twentieth birthday. Karen Brieg was also captured.

Now I experienced on my own body almost everything I had read about in illegal accounts: a dramatic arrest, a hysterical house search, warning shots, handcuffs, interrogation, the ‘third degree’, blows and kicks and solitary confinement…

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

The solitary confinement – and “being the helpless victim of the whims of those in power,” as she later wrote – made a lasting impression. “All you could do was sit there in isolation and with a total lack of any stimuli. No reading material, nothing.” To entertain herself, she unraveled her sweater and wound the wool into a ball, then played with that. She also read the stained German newspapers that her food came wrapped in. The guards taunted her and threatened to tear off her fingernails if she didn’t talk. Like so many other victims of solitary confinement, she could only last so long before mentally cracking.

One night when everything was chaos in my mind, I screamed out loud in fear and helplessness in my solitary cell – but no one came. It was then I promised myself that if I survived this I would work with music for the rest of my life. And then I felt a strange calm: light, warmth and love were all around me. I was no longer alone. This was the turning point in my life.

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

That night she had a transformative, almost mystical experience. She heard music coming from within herself. The following morning, she took a buckle from her garter belt and began scratching out staves and notes on the prison wall.

When the Commandant discovered this vandalisation of a solitary confinement cell loaned by the Danish State, there followed a sound collage of shouting and screaming, the tramping of boots, the rattling of chains, the slamming of doors and the ominous jingle of keys… I reacted very intensely to that. But suddenly the Commandant changed his tune: he had noticed my interest in music (my cover story was all about music – I had chosen the name Wagner – and about the teacher-pupil relationship between Karen Brieg and myself), so now the Commandant decided that he would make sure that the Red Cross brought me music paper and writing utensils so I would refrain from violence and would not dirty the wall any more. “Ich bin ja auch Musiker [I’m also a musician],” he mumbled almost inaudibly and disappeared quickly. When the parcel arrived I stared at the label almost in a trance: in war and peace, compassion …

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

*

After her initial arrest, she was eventually transferred to Denmark’s Frøslev Camp. It was not a labor camp and conditions were, relatively speaking, acceptable. Here Else Marie lived with many women in the barracks instead of alone in solitary confinement. (She later marveled at how her arrest led her to befriend so many extraordinary women she otherwise wouldn’t have met.) That said, imprisonment there was still dangerous: 1600 of the 12,000 prisoners who passed through Frøslev were later sent south to German concentration camps, where at least 220 died.

Else Marie and Karen Brieg did their part to lift the spirits of her fellow prisoners by making music when the Germans weren’t listening. Brieg transcribed Danish songs for a three-part women’s choir, and Else Marie composed Schlager music, a light and catchy genre that exploded in popularity after the war. She planned to make money by selling these songs once released, with the hopes they’d pay for her further musical education.

Her fellow prisoners were impressed by her abilities:

One fine day, some comrades who had been consulting with Karen came into the living room. They had decided to invest in me – they didn’t say if, but when we got out of there. Then I was to live in Copenhagen and attend the Royal Danish Academy of Music. My gratitude as I write this is as boundless and wondering as it was then when my comrades stood there in Room 8 and gave me a brand new life. I can never thank them enough.

Does all this sound like a fairytale? Well, it is. It all came true. We were released on 5 May 1945 – and after the intoxication of freedom (in more than one sense – that is no secret), I moved to Copenhagen and passed the auditions for the Academy in December 1945.

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

While at Frøslev, Else Marie met a man named Henning Pade. As legend has it, they were only able to communicate by throwing crumpled paper notes over barbed wire fences. They were secretly married in 1946, because it was considered inappropriate for a married woman to study at the Academy. They had two sons, one in 1947 and another in 1950. She found the role of housewife difficult to play; she was so often absorbed by her music. The marriage dissolved in 1960.

The defining event of Else Marie’s creative life occurred in 1952, when she heard a radio program about musique concrète and its pioneer Pierre Schaeffer. Finally here, out of nowhere, were the sounds that she had always imagined in her head, that she’d heretofore been unable to express or reproduce. She wrote to Schaeffer, desperate for more information. Soon she traveled to Paris in-person to meet him.

My sister in law lived in Paris and I stayed with her often during vacations. She managed to get an audience with Schaeffer and we were invited to his private home. I said she needed to come with me as an interpreter. So off we went – that was some experience. His apartment was completely crowded with furniture. He had this Wagner-style, excessive, pompous plush furniture with tassels and whatnot. It was so much fun! His speakers were hanging in the corners, shaped like giant ears. I went and sat on the sofa next to my sister in law and she said under her breath, “You must not get ill!”, because when I met great people, I could feel faint! He started to talk and he had such strong black eyes as he stared straight at me, and so he spoke faster and faster and eventually I started to sway and then I could hear my sister in law whisper, “Don’t you dare!”

“Else Marie Pade” by Anne Hilde Neset, The Wire, August 2013

The meeting led to Else Marie becoming a Schaeffer student. “He was never hard to me,” she remembered, “but if a student exhibited hesitation or doubt, Schaeffer would not leave it alone and ask again and again.”

Upon her return to Denmark, she found that none of her colleagues were interested in pursuing this new genre. If Else Marie was going to write musique concrète or (later) electronic music, she’d have to do so alone, especially being a woman.

From an interview with her late-in-life collaborator Jacob Kirkegaard:

JK: Did you in your professional life have close contacts with other composers in Denmark?

EMP: Well… we could find some common ground and have conversations, but it never developed into any really significant deep friendships.

JK: How about other women composers?

EMP: No other women composers. There were just men!

JK: How was that for you?

EMP: It was perfect!

JK: Ok! (smiles)

EMP: Because we could have conversations, just like you and I are having right now. It was all about finding out if we had any musical ideas in common or if we could present new discoveries to each other.

JK: So you never missed having other women around in these circles?

EMP: NEVER, (laughs) I’m very sorry if this sounds bizarre.

JK: No, I don’t think that’s strange at all. It’s just how you experienced it at the time. These are issues that are very relevant today; we are much more aware of the issue of gender etc. Something that was of course very different back in those days. People today are interested in knowing these things, especially since you are not only a pioneer of electronic music in Denmark, you are also a woman who was active as a composer in a very experimental field during a time where most women were at home, behind the kitchen stove.

EMP: Yes that is absolutely correct! Ah, and I was of course accustomed to that mentality from my life at home. It wasn’t like I experienced a great resistance to my activities, It was more like I could sense an undertone of ridicule, like “what is this silly stuff?” and “is THAT supposed to be music?”

JK: Did you sense or give it much thought that if you had been a man, with the same ideas about sound, that you would have been met with a more benevolent and open attitude in Denmark? Did you think about being viewed differently because you were a woman?

EMP: That is of course a given! The view of the generation of my parents was still very dominant at the time. Today you don’t have to deal with these things.

“Else Marie Pade”, JaJaJa Music

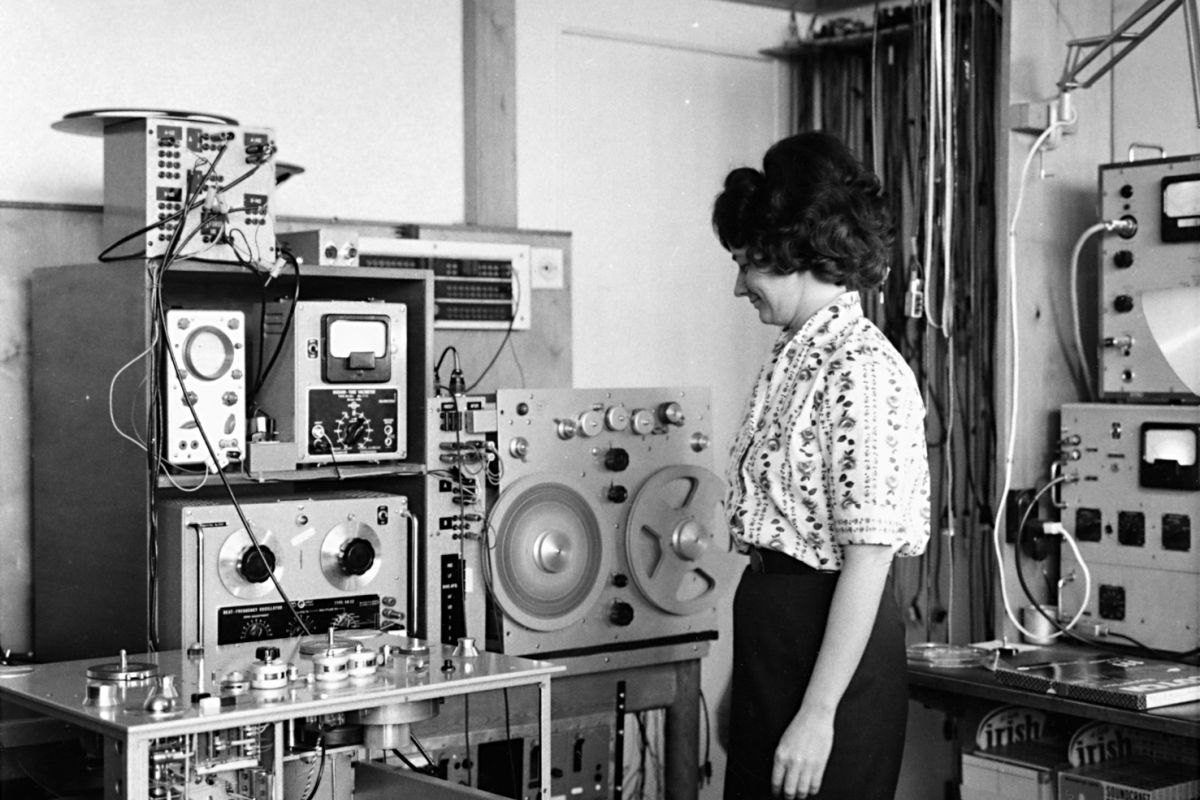

In the 1950s she began working as a producer for Danish Radio, and in the absence of support from local composers, she collaborated with technicians and sound engineers instead. “I was up in their studio all the time asking them questions: What is this? What does that mean? And so on. And they were so sweet – they thought it was wonderful that someone came and asked them things because no one cared what they were doing. There sat Denmark’s best engineers and no one cared to speak to them!”

When she began writing electronic music herself in the early 1950s, she became the first person in Denmark, male or female, to do so.

A string of fascinating works followed. The first was En Dag Pa Dyrehavsbakken, or A Day at the Fair. It was inspired by time spent at Dyrehavsbakken, a park just outside of Copenhagen. She described “the variegated, joyous and distinctive soundworld that surrounded me, and suddenly I understood exactly what Schaeffer means when he so often says: ‘A perfect universe of sound is at work all around us.’ Déjà vu: my childhood world. Where I stood, the market scenes from Stravinsky’s Petrushka sounded all around me in concrete music.”

The day after this lightening bolt of inspiration hit, she began work on a synopsis. Eventually video and concrete music were assembled to create a single work, and on 8 August 1955 En Dag Pa Dyrehavsbakken received its premiere on Danish television.

This was only the first in a series of striking and imaginative musical projects. In her adaptation of The Little Mermaid, the sounds above the water consist of recordings drawn from real-life, while beneath the waves, we hear only manufactured electronic sounds. While creating the work, Else Marie and engineers lowered microphones underwater to ensure an authentic aquatic atmosphere.

Symphonie magnétophonique (titled in French as an homage to her mentor Schaeffer) was a twenty-minute piece describing 24 hours of life in Copenhagen. She drew heavily on the aural memories she’d made as a child, quoting the sounds of alarm clocks, showers, the City Hall clock, street music, radio news, teatime, breezes, and lark song.

Syv Cirkler, or Seven Circles, was commissioned by San Francisco based sound artist Henry Jacobs, and was inspired by a visit to the planetarium. It was precisely, expertly planned: “I wrote Seven Circles, which is based on a seven-note row, each note furnished with its own tonal colouring and its own speed, from slow to fast. The circles come in one after another, and once all seven are in motion they accelerate, reach a climax and are drawn back to the tonic in reverse order. The work was purely electronic. Seven Circles was very quickly sent by airmail to San Francisco.”

In the early 1960s she also wrote a work inspired by Faust, as well as a television ballet called Grass Blade, collaborating with dancer / choreographer Nini Theilade. And in 1970 she wrote her most aggressively arresting work yet, a piece called Face It, in which a drum beats and a voice intones in Danish over and over again: “Hitler is not dead, Hitler is not dead.” A second voice – angry and cruel – is sampled, first in short spurts, then in increasingly longer ones. It’s a gut punch when your brain finally, suddenly recognizes these broken pieces as samples of Hitler himself: he has been present in the ugliness all along, hidden in plain sight. Else Marie may have survived her brush with authoritarianism, but she clearly feared the fascism of the future.

*

She tried to avoid doing this experimental work in isolation. In 1958 she traveled to the World’s Fair in Brussels to meet with European colleagues. Highlights included hearing Varèse’s Poème électronique and the premiere of Berio’s Omaggio a Joyce. “I had a fantastic time. I met Boulez, Stockhausen and Pousseur. It was amazing to be among people with similar interests where you felt very much on the same wavelength.”

Her friendship with Stockhausen led to her attending the famous Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music. Despite being one of the few women present, she claimed in interviews that she never felt unwelcome. Stockhausen was genuinely impressed by Else Marie’s work; he actually used her piece Glasperlespill (Glass Bead Game) as an example in his famous lectures.

She tried to bring the camaraderie that she felt at Darmstadt back with her to Denmark. In 1958 she co-founded an organization called Aspekt, meant to support experimental artists of all kinds.

But despite her best efforts to stay connected, her artistic isolation began to increase in the 1970s. Emerging digital technology didn’t appeal to her in the same way as the equipment that she’d used in the 1950s and 1960s. She didn’t possess the academic credentials that were an increasingly necessary prerequisite for entry to the avant-garde world. And surely sexism played its own role.

Luckily, though, she was not forgotten, and unlike so many women in music, she lived to see her own revival. A Danish music journal wrote about her in 2001. A radio documentary followed. That led to a CD release of some of her compositions, then another, and another. Remixes of Syv Cirkler were created; one was even broadcast on MTV. (This delighted Else Marie to no end.)

By the time she collaborated with Jacob Kirkegaard, she was acknowledged in Denmark as an important forerunner of electronic music. Thomas Knak said in 2002, “Turns out, she is the grandmother of all of us electronic musicians. But it’s kind of funny, because none of us knew until recently that we actually had a grandmother.” In her late seventies, she finally found partners for the creative dialogue that she’d been craving her whole life. The 2012 Wunderground Festival performance ended with a standing ovation that brought the composer to tears.

In August 2013 Anne Hilde Neset wrote a profile of Pade for The Wire. When Neset arrived at the retirement home and explained why she was visiting, the nurse smiled. Else Marie was “such a busy woman, the celebrity of the house.”

While there, photographer Mikael Gregorsky took a striking portrait of Else Marie. She sits in an easy chair, her beloved mid-century tape recorder visible behind her shoulder. She clasps a small bust of Beethoven to her heart. Here is a revolutionary who never forgot her roots.

Else Marie Pade passed away on 18 January 2016 in Gentofte, Denmark. She was 91 years old.

And now this tale is coming to an end. The story of the many mysterious compositional paths has come back to its starting point.

A perfect universe of sound is at work all around us.

“The Compositional Possibilities Are Endless” by Else Marie Pade

*

As always, a huge shout-out to the patrons who make this series of articles on forgotten musical women possible! It wouldn’t happen without you.

If you want to support the series for as little as a dollar a month, click here. Entries typically come out every other Wednesday.

Sources:

English Wikipedia entry on Else Marie Pade

Danish Wikipedia entry on Else Marie Pade

Wikipedia entry on Frøslev Prison Camp

“Else Marie Pade”, by Anne Hilde Neset, The Wire, August 2013

“Else Marie Pade”, KVINFO entry

“Else Marie Pade”, Jajaja Music

Kirsten Sterling interview with Else Marie Pade, September 2005

Sound on Life documentary, directed by Iben Haahr Andersen and Katia Forbert, 2006

This is absolutely riveting. I found myself entranced listening to the shifting sounds in the performance in the documentary. “Music of the spheres” kept popping into my brain.