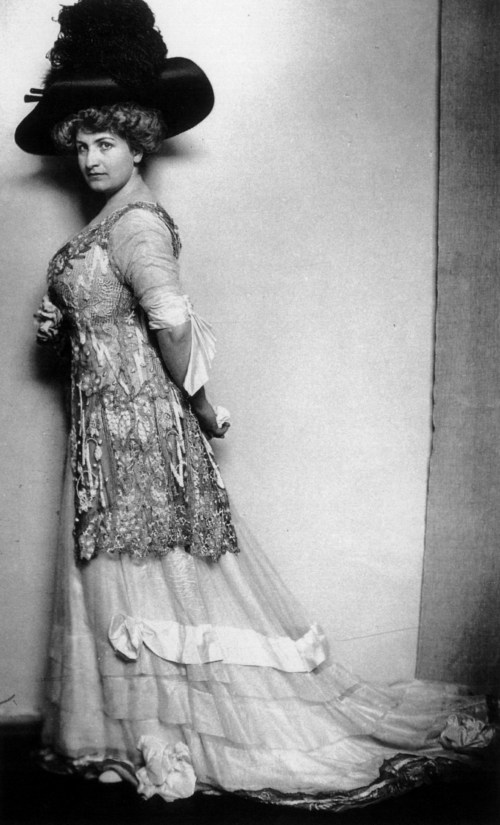

Alma Mahler

I

In January 1918, Alma Mahler Gropius saw writer Franz Werfel at a performance of her dead husband’s fourth symphony.

During the concert, Alma and Franz exchanged long, lingering glances.

At intermission, she brought him home, cheating on the man she had cheated on Mahler with.

The affair didn’t end there. As winter melted into spring, Alma realized that she was pregnant. It was yet another upheaval in a year (an era!) full of them, as the Great War wreaked havoc on European life. Alma’s husband, architect Walter Gropius, had been severely wounded in battle and was recuperating in Vienna. (There was even a chance he was the father of the baby; he had returned home on furlough at Christmas.) Her lover Franz Werfel had been conducting a lecture tour in neutral Switzerland, but in March received orders from the War Press Office to return to Vienna. Everything, it seemed, was in flux.

In the summer, Alma left the city and her love interests, decamping to the family’s second home in Breitenstein. (Mahler had chosen the land as the place where he wanted to retire; Alma only built there after he died.) Franz Werfel followed. He and Alma agreed to be discreet.

Other visitors came, too. On July twenty-seventh, Alma entertained a wealthy sugar manufacturer’s wife named Emmy Redlich and her teenage daughter. Alma trotted out her own teenage daughter, Anna, and together Alma and Anna played an arrangement of Mahler’s eighth symphony, commonly known as the Symphony of a Thousand, on a single harmonium. The Eighth ends with the words:

Here the indescribable / Is accomplished / The ever-womanly / Leads us above.

It was a late night, but finally the guests went to sleep and the villa fell quiet. Franz Werfel slipped from his bed and into Alma’s. The sex was violently passionate. “I didn’t go easy on her,” Franz later wrote. They finished, he left, and Alma drifted off to sleep.

The next morning she awoke as if from a dream, her body soaking in a warm, sticky pool. She found herself screaming as she rang for her maid. The rough sex had caused her to hemorrhage.

Franz ran across fields to find a doctor. He found a small-town physician who worked at the local sanitarium. Alma, her body weakened but her will strong as ever, took one look at him and demanded someone better qualified. By this point, Walter Gropius was rushing in from Vienna, a gynecological specialist in tow. Franz and Walter even passed each other at the train station, but Franz managed to slip away unnoticed.

The ongoing European carnage meant a shortage of ambulances, so Alma had to be transported part of the way to Vienna in a hearse. On August first, she arrived at the same hospital Gustav Mahler had died at. This was where the doctors decided they had no choice but to induce labor. That night, in grisly bloody agony, she gave birth to a premature baby boy. Walter Gropius stayed by her side through it all.

Despite all odds, both mother and son survived the night. When Franz learned the fates of his lover and child, he wrote a letter: “You holy mother! You are the most magnificent, the strongest, the most mystical, most goddess-like I have ever encountered in all my life…”

On August 25th, when Alma and Franz were speaking on the telephone, Walter Gropius walked into the room unannounced, and suddenly he understood everything.

One might have expected a scene to ensue, but there was none. The sexual triangle staggered on. Alma knew she didn’t love Gropius anymore, but in October, she slept with him again anyway. He had acted with such dignity and calm after discovering her betrayal that he was difficult to resist. New reservations about Werfel began creeping to the fore, especially after he began involving himself with bloody revolutionary politics. Alma openly acknowledged she had no idea where she or they were going.

*

During the winter of 1918-1919, her still unnamed son developed a swelling in the brain. Once again, the doctors decided that their only hope was a painful medical procedure. They would attempt to pierce the swelling and drain it. The first try didn’t work. “If only our child would recover, then all will be well,” Alma fretted. Her wish was unrealistic on several levels. Later procedures proved equally painful and ineffective. Her baby was doomed.

In February, Alma resolved to cut herself off from Franz Werfel. “I have no desire ever to see him again,” she declared. (She later married him.) Desperately flailing for answers, she hit upon the explanation that their boy’s illness was caused by the “degenerate” seed of the Jewish Franz Werfel.

She finally christened the baby Martin Carl Johannes, and ultimately left him in the hospital to die in the care of professionals. In the spring she left Vienna to visit Walter Gropius in Berlin and Weimar. He had just founded an art school called the Bauhaus, which would have a profound effect on twentieth century design. “I’m deeply attached to Franz,” Alma mused that spring. “We have a frighteningly powerful love for each other, and hate each other with a passion. We torture each other too, and yet we are happy.”

Martin died on May 15. Alma wasn’t present. She never wrote a single word about him after his death; it’s as if he disappeared from the earth and her heart simultaneously. Franz Werfel found out about the death in a letter from a friend. We don’t even know anything about Martin’s burial.

All we know about his brief life is its muddy origins – its bloody start and finish – the sexual violence that triggered his birth – the excruciating physical pain he and his mother endured – the simultaneous joy, sorrow, and anxiety his existence engendered – and the total void of emotion that came after it.

II.

Mahler has never been one of my favorite composers. I’m skeptical of canvases as large as his.

But after I read the horrifying story of Alma’s son, I felt as if a door had cracked opened. Maybe tempestuous Alma, simultaneously so seductive and so repulsive, can help me make sense of this overwrought aural world. When you read the real-life history, suddenly the violent extremes of Mahler’s music stop ringing so false.

In February 2000, Alex Ross wrote in an essay in the London Review of Books: “One starts to wonder: ‘Is there such a thing as too much Mahler?'” As the years go by, and the discs stack up, that question becomes more and more relevant.

And yet despite the music’s ever-increasing omnipotence, a Mahler symphony cycle remains just as massive a gamble as ever: artistically, logistically, financially. The stakes are even higher when the results are being committed to disc…to veritable immortality. A conductor and an orchestra would have to be as egomaniacal as Gustav Mahler himself to think they have anything worthwhile to add to the ever-expanding catalogue.

Sometimes, though, the very best of the egomaniacs are right. Enter the Minnesota Orchestra and music director Osmo Vänskä, and their planned multi-year survey of the Mahler symphonies for the BIS label.

I’d be skeptical of a Mahler cycle with nearly any other orchestra and nearly any other conductor. But for the past fifteen years, Osmo’s Minnesota Orchestra has proven itself in a few key ways. It can say something startlingly new in well-worn repertoire, as evidenced by its beloved Beethoven cycle for BIS. It is smart and adaptable enough to bring to shattering life wildly divergent sound worlds, as demonstrated by its Grammy-winning Sibelius cycle, in which it so effortlessly roamed the gamut of moods from luxuriously romantic to grimly ascetic. It catches detail; it knows how to propel narrative; and it sounds disarmingly beautiful. And it can play like its life depends on making a visceral impact on listeners…maybe because not too long ago, it literally did.

So a new musical journey is beginning in Minneapolis. And that means that as a listener, I will have to come to terms with Mahler. This won’t be easy. I’m repelled by the self-certainty of a man who composes a seventy minute symphony then gleefully writes about it to his wife: “Heavens, what is the public to make of this chaos in which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble into ruin the next moment? What are they to say to this primeval music, this foaming, roaring, raging sea of sound, to these dancing stars, to these breathtaking, iridescent, and flashing breakers?” Despite my skepticism of foaming sounds and flashing breakers (what the f*ck?), I’m choosing to trust that the Minnesotans have something important to say – to scream – about Mahler.

“I’m not a Mahler girl,” I told principal cello Tony Ross before Friday night’s performance of the fifth symphony. “Convert me.”

III.

Principal trumpet Manny Laureano kicked off the cycle with four searing notes, heavy with connotations of Fate, and Turmoil, and Destiny. When the rest of the brass blossomed around him, the effect was apocalyptic. For the first time, I could maybe believe the bombast.

The winds and strings followed soon after: weary, comparatively dilute, elegant and sophisticated. The instruments muttered about. Then, with a quick jab of Osmo’s baton, they suddenly swept from a tragic somber march into high circus-like extravagance.

Throughout the night, the one thing Osmo and his orchestra did best was navigating the turns of mood, volume, and character that could so easily cause whiplash. (Like I said, this orchestra is good with narrative.) The cellos, for instance, ripped into their second movement string crossings with such savagery I feared for bows. Then a few minutes later when they had their big quiet tender solo, you could practically hear hairs standing up on the backs of arms. Everything else after that demonstrated the crazed, wild-eyed wonder of contrast…the violence of veering between deafening screams and whispered caresses.

Another stand-out solo brass moment came toward the beginning of the third movement, as the sheer sonic weight of Michael Gast’s horn shook the foundations of the hall. Most orchestras and maestros seem to approach this movement as a Serious Symphonic Slog (TM), but this version had a bewitching fleet-footedness about it. It’s not that it was taken at a particularly fast tempo – it wasn’t, and there was weight – but that weight swung. Portions of the scherzo even reminded me of Ravel’s La Valse, where a seemingly sweet dance starts flirting with destruction, to terrifying effect. The pizzicato waltz sounded like a ghost dancing, every bony plunk perfectly judged. When the triumphant main fanfare returned, it was as shocking as watching a painter cheerfully whitewashing a bloody crime scene.

Then the spellbinding adagietto movement for strings alone. Legend says it’s Mahler’s love song to Alma, but apparently the only evidence we have of that is testimony from Bruno Walter. (So much we think we know about Mahler is actually second or third hand.) (Thanks in large part to Alma…) So what is this music, besides ethereal? Is it a portrait of sex? Sensuality? Death? (It certainly entered twentieth century musical history as a kind of requiem…) Or is its only purpose to be the most beautiful contrast of the night? I thought of little Martin as I listened. The violas began so quietly, you saw bows moving before you heard sound. But even in the quietest moment, the players never sacrificed their beauty of tone. Friday night’s tempo was, to be blunt, too slow; the adjustment on Saturday was a relief, and lent cohesion to the line.

The fifth movement started like a cat stretching and awakening from a nap. When the drone finally came in to accompany the first big theme, smiles were exchanged across the stage. I know what those smiles mean: a supercharged gallop to the end, executed with special Minnesotan panache. Musical lines crossed each other and surged forth in truly glorious fashion. The adagietto theme transformed itself into giddy swells. At every new climax I felt windblown by the sheer force of sound.

This is some frighteningly unstable shit.

It might be hard to sell the hypersexualized energy of Mahler’s fin de siècle Vienna to Minnesotan audiences. (And to me…) But when the music is played as marvelously as this, it’s very hard not to be seduced. The standing ovation was one of the quickest of the season. Torrents of applause rained down on every player as Osmo singled out each instrument for cheers. Every holler was deserved. The disc should be a good one.

*

Alma once wrote of a trip she took in 1910:

The only day I spent by myself in Amsterdam was May 18, the anniversary of Mahler’s death. I went to the Rijksmuseum and saw the Rembrandts, the Vermeers, the Ruysdaels. I was glad, for once, to be alone, and yet I would have liked to discuss the pictures with someone. Why was I so alone? Had all of them withdrawn just to be tactful?

I did not miss Mahler, and my attempts to put myself into a mournful mood failed miserably, I have no feeling for dates, so days of remembrance have no reality for me.

I wrote in my diary:

It is only by myself or with Franz Werfel that I feel quite myself. With him, too, all reflections fall away. It was the same with Gustav Mahler; but he has been dead for almost ten years.

I felt I no longer had the right to hold court as “the Widow Mahler.” I was getting tired of it, too.

In addition, I was not always in full accord with his music. It frequently seemed alien to me, insufficiently architectonic and often too long . . .

I was moved by the fact that Alma Mahler (of all people!) found Gustav’s music “alien”: that she “was not always in full accord with” it. Her blunt apathy speaks to me much more clearly than her husband’s babble about flashing breakers.

Seeing the emotions of Gustav’s symphonies through Alma’s eyes has been illuminating. It has bought me more time in this world of contrasts, this heady universe of extremes. And who knows? If the Minnesota Orchestra keeps playing these symphonies this passionately, this dazzlingly, I might ultimately find myself in love.

Before now, everything I knew about Alma I’d learned from Tom Lehrer. :)

I think a lot of people have had that experience! Thrillingly, she’s way more interesting than the song suggests! Here’s a profane blog entry cataloging her many sexual exploits: https://historicalscandals.wordpress.com/tag/alma-mahler/

If I remember correctly, Mahler showed the Adagietto to Alma first at the piano. Did she know it was their great love song? Please clarify this, Emily.

We were in the Hall on Thursday morning. The mighty Minnesota and conductor provided an unforgettable concert. As the music washed in and through me, I had flashbacks to other great Mahler nights. I was so touched that it was difficult to talk or even look at anyone while coming back to Earth. One floated, not walked from the Hall.

Thanks for the fine history lesson and concert review.

I hadn’t read that story about the adagietto. Maybe you’re right! I read in a couple of places that Bruno Walter said he’d been told by Alma and Gustav separately that it was their love song, and that that’s the only information we have on the subject. It seems like only the Mahler experts – and I’m sooooo not one – can know the truth of some of these stories!! If anyone has any sources that disprove what I read, do post a comment! Thanks for your lovely words.

Emily,

This is excellent. I do have a suggestion though. Take a little time off to read up on what was going on in Europe before WW I, especially Germany, Austria, France, etc. The cultural things–not just music.

I’ll get back to you next week.

Lisa R

What books do you feel are the most helpful when you’re self-educating on the topic? I’m putting that research topic on the back burner as there are other major projects brewing (TBA!), but I’d like to return to the subject before the next Minnesota Mahler performance in November…

Emily,

Books? My dear Emily, we have computers now!! Seriously the first thing I would do is to do a search on the cultural life of Europe from 1900-1914 on the internet. Then ask the internet for books on this subject.

Think of it this way: in the music world between 1900 and 1914 we had 1) Stravinsky’s Firebird and the Rite of Spring, 2) Schoenberg was working on atonality, & 3) Bartok and Prokofiev were writing some pretty “scary piano music” Yea!!!!

More to come!

I ask about books because for the way I learn, for whatever reason, the Internet doesn’t take the place of exhaustively researched books. My best learning experiences about cultural history come from pre-concert talks, exchanging ideas with friends, and books. The Internet is perfect for narrower research, or for getting the flavor of an era using vintage Google Books. But for learning about broader topics, especially European history and culture, I find the Internet less useful. But folks’ mileage will vary, and I think a lot depends on learning style.

I can relate. I was dragged, kicking and screaming to using the computer at all and originally wanted it only to compose music. Now I can’t live without it. In that case, get the to your best local library, and / or an internet source of books on the subject.

The whole reason I bring this up is because when I was in college – well those were the days of the hippies and the protests of the Vietnam war, yet a lot of what people were reading (get this) came from writers and poets some of whom were writing almost revolutionary books and poetry and from all over Europe and this literature was originally from 1900-on: In W B Yeats poem “An Irish airman foresees his death” (this was during WW I) is the quote “Those that I fight I do not hate, Those that I guard I do not love.”

In other words; All of Europe was in turmoil at the beginning of the 20th Century and Alma Mahler was literally being “carried along in the flow” of what we would call “wild and crazy times.”

Emily,

I suggest you read the “The Proud Tower” by Barbara Tuchman.

Kurt Rusterholz

I really enjoy your writing Emily, and I like your pride in the Minnesota Orchestra.

I am looking forward to hearing this recording and wish I could have heard the performance. I am a Mahler nut. Perhaps it started because I am a trumpet player (and hearing Manny Laureano live is something I must do), but his music goes deeper than that. I think he is the greatest of all composers now – Mahler 9 is the most profound, personal and artistic expression I know of. Read Ken Woods if you haven’t already.

One of the other things that make Mahler great to study is his composing huts. I’ve been to all three, and they each have a distinct personality. And how amazing it is to sit in the room where this incredible art was conceived!

Mahler 5 is the most approachable. And it’s a great showpiece for a virtuoso orchestra. I’m still searching for a perfect recording, so it’s great that the Minnesota version is coming out soon. Right now it’s Chicago and Abbado. For brass players, the Chicago/Solti first recording is special – it was recorded at the zenith of the greatest brass section ever’s power. And for trumpet players, Adolph Herseth is our God. But the recording is not digital, and that makes a huge difference.

Just as curiosity Emily, how many other of the world’s great orchestras have you heard, and how do they strike you when you hear Minnesota again? O consider San Francisco “my” orchestra, but the hall and conductor can make a huge difference. Los Angeles and Dudamel in Disney Hall is pretty special, too.

Live in-person? I’ve heard St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Met Opera Orchestra, and Chicago Symphony. All great. But for me there’s something about Minnesota. They play as if their lives are on the line. It’s impossible for me to separate how much is this is sentiment because I love the people onstage so. They’re my second family. But I saw how the audience reacted to them in New York. And apparently it’s not all sentiment on my end. :) Thanks for the comment!!!

Your writing makes me want to hear Minnesota. And the connection you feel is what all audiences should feel when listening to their home orchestra, whether it be The Vienna Phil, or the Tiny Town Community Orchestra. There is a difference in quality, but the emotional connection heightens your appreciation.

I think Mahler’s extremes will win you over in the end. In the hands of a virtuoso orchestra, it’s just to damn awesome to hear.

You SHOULD hear Minnesota! Mahler Resurrection closes out the 16/17 season…..

Sold! Favorite piece of music. Not a religious guys, but that piece makes you religious.

Let me know if you end up coming to town! I can get you recommendations on places to stay and stuff.

Scott: Personally a live performance of Mahler’s 3rd Symphony was a much more spiritual experience for me than any performance of # 2. But you do NEED to be in a hall with perfect acoustics for this.

Lisa Renee Ragsdale

It can be! That’s like debating your favorite child for me. The 3rd mvt. Post horn solo, the final movement…all sublime. I visited the hut where it was composed and it’s easy too see why the music is so moving.

I’m late to the discussion, but, speaking of the 3rd Symphony … For the ultimate in a pre-concert experience (which you can enjoy at home on YouTube), the documentary “What the Universe Tells Me” can’t be beat. Amazon’s official review of the DVD reads: “What the Universe Tells Me is probably the deepest, most painstakingly detailed but also approachable attempt to decipher the inner dynamics of a complex work of art [Mahler’s 3rd Symphony] ever entrusted to any recording medium.” And the narration is by the wonderful Stockard Channing. Highly recomended!

You are a magnificent writer.

This is magnificent.

Wow! Love your passion for live music played well and the ambivalence when examining the stories behind the music. You write very well. Reminds me of Leonard Bernstein’s passion for getting the word out about the joys of music played well.

I flipped out over Mahler the first time I played the Wayfarer songs in youth orchestra, and my fate was sealed when I did the 1st Symphony in college. I adore the extremes, and the performances I don’t like are those that try to round off the edges; after hearing Bernstein and NY Phil do 1 live on tour, I couldn’t listen to my Ormandy/Philadelphia LP of it any more. The last time I heard MTT and SFS do 5, I honestly thought Mark Inouye was literally going to blow the roof off Davies. In a good way. I find the way all his music draws me into its universe, and out of my own, to be very cathartic. This is not always a good thing when I’m onstage, of course, as the tear tracks in my varnish from my last go-round with 2 will attest. And yet my other favorite composer in the world is Brahms – go figure.

Thanks for sharing!! It’s so amazing to hear about people’s visceral connection to Mahler. I’ve heard the word cathartic used a lot when talking to people about this music, especially musicians.