Sometimes my cat swallows several times in a row and starts licking her lips. I, having lived with her since 2012, understand that this is a sign to grab a roll of paper towels, because she is about to hork up a hairball.

In much the same way, when a major American orchestra launches a gauzy website under the guise of informing the public about a labor negotiation, I, having followed this industry since 2012, understand that this is a sign to grab a roll of paper towels, because said orchestra is about to hork up a hairball.

The SF Symphony Forward Site

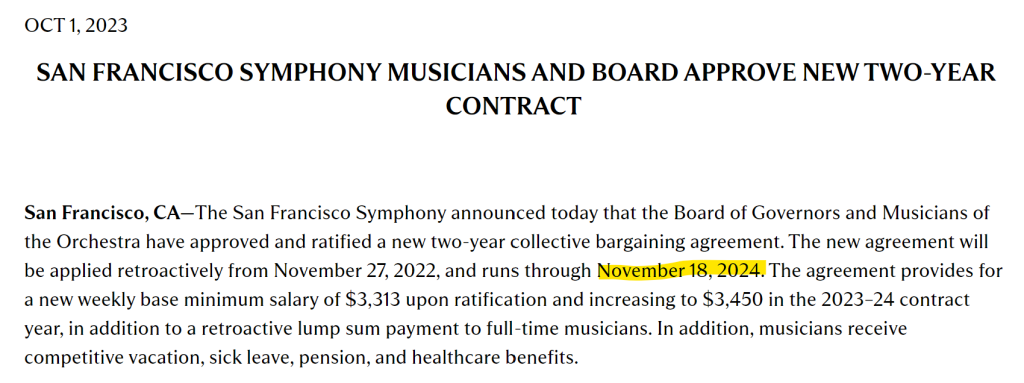

Over the past year or so, the management of the San Francisco Symphony has been attempting to negotiate a new contract with its musicians. This process has not gone smoothly.

We can guess that matters are about to come to a head because the organization recently launched a new website called SF Symphony Forward, which you can see here.

I’m not sure how the acronym for this website is meant to be pronounced, but I am calling it “sfsf”, which is an approximation of the vocalization I make while cleaning up after my cat.

I find the SFSF website fascinating. I could write multiple theses about it. (Unfortunately for everyone, if time permits, I may.)

The reason I’m so obsessed? It’s a management-run site about orchestra negotiations that seeks to center patrons. Its very first sentence reads:

Our goal is for the San Francisco Symphony to be a thriving nonprofit organization that exudes creativity, performs at the highest level, and has a broad and passionate patron base.

My italics.

And look at the background image. It’s the audience in the hall.

Wait, isn’t centering patrons good?

Yes, centering patrons is good. Collaborative is good.

The problem is, the San Francisco Symphony management team has spent a year being anything but collaborative.

They want to sound like they’ve centered patrons, but they’ve never actually centered patrons in the past, or explained how they’ll center patrons in the future.

If you’re new, here’s a brief summary of the backstory so far. Note the distinct lack of patron-centering throughout.

- In December 2018, the San Francisco Symphony signed star conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen to serve as music director, beginning in the 2020-21 season. 1 By all accounts, most patrons were thrilled by the choice, as was the board, which expressed eagerness to support him and his ideas.

- Unfortunately, around the time of the pandemic, Salonen and the board appear to have had some kind of falling-out. In short, management hired him for his ideas, then came to loggerheads with him over the realization of his ideas.

- A house divided against itself cannot stand, and in March 2024, Salonen issued a shocking statement: “I have decided not to continue as Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony, because I do not share the same goals for the future of the institution as the Board of Governors does.” This is not the way these kinds of things are traditionally handled. It was announced that Salonen would serve out the remainder of his contract through June 2025, then depart. 2

- The symphony’s leadership team didn’t treat this loss of talent as an institutional emergency, or express any remorse, which rubbed many patrons the wrong way. If anything, leadership seemed to be relieved that he was leaving.

- After driving away Salonen, the leadership team began telegraphing an organizational change, giving a number of interviews about their new strategy in the summer of 2024. In a bid to save money, they floated playing fewer concerts, investing less in new music, pausing touring, etc. (That said, a $100 million hall renovation was still being actively discussed.3)

- The leadership team didn’t win over many folks in the court of public opinion. Lots of patrons felt sad, angry, or confused about what was happening. It didn’t help that the leadership team was routinely coming across badly in their interviews.

- At the end of a June 2024 profile, during which the board chair and CEO appeared particularly hapless, business writer Adam Lashinsky went so far as to muse: “Now it will be up to San Francisco audiences to decide for themselves if the moves the current symphony leadership makes to replace Salonen are up to snuff–or if they need replacing themselves.” 4

- Patrons got increasingly angry.

- In June, one showed up to a Salonen concert and flashed a sign that said “F*** the board” in Finnish. She was told by the orchestra that if she ever did such a thing again, she might be banned from the hall. She told the press she was contacting the ACLU to explore her options. 5

- In September, the leadership team pursued something that felt an awful lot like a dry run for an orchestral labor dispute with the singers of the San Francisco Chorus. 6

- The orchestra’s first Salonen-less 2025/26 season was released last month. It has been roundly panned for its lack of cohesion and artistic vision. There is a sense that something important about the identity of the ensemble disappeared with Salonen. Critic Joshua Kosman wrote an article for the San Francisco Chronicle titled “S.F. Symphony’s next season has a gaping hole — and it underscores the institution’s crisis.” 7

- To sum, the current leadership team at the San Francisco Symphony became the first American orchestra to fumble its negotiations so badly that the public started revolting against them before a work stoppage even began.

Now, after six months of relative silence, enter the SFSF website, which has carefully honed its message to appeal to…patrons.

Wow! So does this new SFSF site meaningfully address any of the concerns that made patrons rebel in the first place?

No.

Is it normal for orchestra managements to create these kinds of sites during labor troubles?

Yes. If negotiations go well, they will be conducted privately. If things get a little spicy, a quote or two might be released to the press. After the negotiation is finished, a press release hailing the achievement will be posted on the orchestra website’s press room page. Then everyone will move on with their lives. This is how the contract negotiations at other large American orchestras played out this past season.

On the other hand, if shit is about to hit the fan, and a labor dispute seems possible, a management team will hire a PR firm, buy a new domain name, and build a new website there to frame the story on their terms.

These management-built sites invariably employ certain dog whistle phrases. They will read innocently to normies just tuning in, but freaks like me know they come from the comms playbook of crises of yore.

“Average compensation”

During adversarial negotiations, orchestra managements like to use the term “average compensation.”

“Average compensation” is a figure that the public has to accept in good faith. Obviously we don’t have access to all the figures used to calculate it, so we have to trust that management is doing so correctly.

This figure will also paint a skewed picture. A handful of principal players can negotiate a much higher salary than their colleagues, due to their increased responsibilities. It’s not an especially enlightening practice to lump them all together, but it does have the benefit of making many musicians look like they’re being paid more than they are.

On the other hand, musicians in a labor dispute tend to prefer using “base salary” as a measurement. Obviously, this is a lower number, which makes the musicians look more sympathetic. But it also has the advantage of being a more concrete number to work with, and it doesn’t rely on management math like “average compensation” does. It also makes comparisons with peer orchestras easier.

“Ten weeks of paid vacation”

Ten weeks of paid vacation? What are we, Norway or another civilized country?

We are not. Here’s the truth. Orchestral musicians in America working at this level, playing this amount of repertoire, don’t get many vacations. They are athletes of their art. They play for multiple hours a day at home every day, even when they’re not rehearsing as an ensemble or performing onstage. Therefore, this is less “ten weeks of paid vacation” and more “ten weeks of working at home.”

As you can imagine, in the past, this framing has been used to paint musicians as lazy and entitled. It has been critiqued for over a decade in patron advocate circles. A blogger friend of mine named Scott Chamberlain wrote an entry about this phenomenon here after the National Symphony Orchestra management team briefly tried a similar tactic in 2024, and that was a rewrite of a blog entry that he’d originally written during the 2012-14 Minnesota Orchestra lockout. There is nothing new under the sun, etc.

“A dedicated administrative staff”

Immediately after discussing musician compensation, the SFSF Finances page veers into a discussion of administrative staff compensation.

Obviously the orchestra won’t come out and say “our greedy musicians are keeping us from paying our administrative staff more.” But it’s also unclear what other conclusion a reader is supposed to take away from the juxtaposition.

Is the staff at the San Franscisco Symphony underpaid? Almost certainly yes, with a possible exception for the guy at the top. “You will know them by their fruits” is solid advice whether you’re religious or not, and I think that the field could have an interesting conversation about the particular fruits we’ve watched CEO Matthew Spivey bear during his tenure so far.

That said, low pay for administrative staff is a major industry-wide problem. It is also a loaded and complicated one, given that the applicant pool for an administrative staff position at a major American orchestra will be very different from the applicant pool for a musician position at the same American orchestra, and obviously the various qualifications for various types of jobs are very different.

Another problem the administrative staff faces is crippling work stress. Now, I don’t claim to know exactly what life is like right now for the SFS’s administrative staff. But I can take an educated guess that it isn’t great. Why? Generally speaking, most people don’t enjoy working inside an organization where stakeholders aren’t working well together. Again, I watched the Minnesota Orchestra’s lockout last from 2012 to 2014. I heard the stories from musicians and administrative staff alike.

If an institution has genuine concern for the well-being of their administrative staff, and can’t afford to pay them what they’re likely worth, the most valuable thing that a leadership team can do is to get everybody rowing in the same direction. It speaks poorly of their captaining ability if they start pitting one oar against the other.

“Business model”

When leadership teams are seeking to shrink a symphony orchestra, they like to refer to the orchestral “business model.” People are generally more receptive to cuts to a business than to cuts to a non-profit.

I once heard Kevin Smith, the beloved CEO who oversaw the post-lockout recovery of the Minnesota Orchestra, say something along the lines of, it’s an orchestra’s job to lose money. The function that an orchestra serves in society is to convert dollars into intangible benefits for a community that are otherwise very difficult or outright impossible to access or assign a dollar value to. A major orchestra is a kind of magical currency converter.

Of course orchestras can’t be wasteful. But there are better terms than “business model” that more accurately describe this process.

“The union representing the members of our orchestra”

Managements seeking concessionary contracts love to insinuate that musicians are dumbass dreamers being screwed over by their union. It’s easier to blame an outside force for any intransigence, rather than the faces that patrons see onstage every weekend.

The reality, however, is that an outside force will not be dictating the terms of this negotiation. The orchestra members themselves, not some faceless shadowy orgiastic cabal, will be voting on whether to ratify their next contract.

“Sustainable”

Orchestra-shrinking enthusiasts love the word sustainable. Sustainability is a kind of spiritual experience for them. They go absolutely nuts for it.

Unfortunately, this kind of for-profit terminology also creates a permission structure for an organization to self-harm, if creative and collaborative people are not firmly ensconced at the top. After all, what’s more sustainable: a symphony orchestra or a quartet? If sustainability is your primary goal, what is the backstop to keep you from shrinking yourself out of existence? And how strong is that backstop — especially when there’s no music director on staff to stand up for the art?

Many orchestras over the past fifteen years have faced cuts made by people obsessed with the word sustainability, to the point where the word has become a joke in the patron advocacy world. It comes with multiple decades of baggage. It’s shorthand for chainsaw. And if the folks in San Francisco using it here don’t know the history of the movement, they aren’t in a great place to advocate for the interests of passionate patrons.

There’s so much more

There’s so much more to dig into here, but alas, I don’t pay my electricity bill with writing about the labor travails of symphony orchestras.

But even if I never get another word out about this situation, I wanted to point out why every patron should approach this site with caution.

They’re talking about centering patrons, but they’re also employing the same language that we’ve seen in past labor disputes, when patrons were decidedly not centered. Beware.

What are the patron takeaways here?

First off, I stand by what I wrote last June in my entry “The Second Problem of the San Francisco Symphony.”

This orchestra has two problems.

The first has to do with whatever financial hole this orchestra is in.

The second has to do with a lack of vision, ambition, and galvanizing leadership, especially in the wake of Salonen’s departure.

The SFSF site talks a lot about the former, but it has yet to address the latter in any kind of useful way.

There’s this chart, I guess, under the VISION tab, but it’s non-specific and uber-corporate. Is this the plan for the San Francisco Symphony, or the mission statement for the Choreography and Merriment Department from Severance?

The paragraphs attempting to elucidate the chart don’t help, either. In fact, this is a whole other blog entry right here. What the fuck does any of this really mean?

*

Here are some potential ideas for patrons to pursue, to gently but firmly push the leadership in a genuinely collaborative, pro-passionate-patron direction.

- Don’t lose sight of the two problems: the financial side and the leadership side. Don’t let concerns about finances eclipse concerns about leadership. They’re connected.

- Push for a town hall with CEO Matthew Spivey and board chair Priscilla Geeslin. Communicate your thoughts to them if you believe that the past year’s shenanigans have damaged the institution’s reputation. Have them explain what they learned from the Salonen meltdown, and what they did wrong. Ask that they clarify what they’re doing to both attract and retain a first-rate music director in future. Make them work hard to justify altering the heart of this orchestra. Remember, they aren’t there to serve the musicians, and the musicians aren’t there to serve them; everyone in that organization is there to serve you. Without the people who buy tickets, this entire project has no point.

- If they say that nobody does town halls, or if they’re too skittish to mount one, you can tell them that Minnesota Orchestra CEO Kevin Smith did it ten years ago after their lockout, and the fact he was the kind of person who did, helped to rebuild community trust more than the shiny SFSF website ever will. 8

- Follow the musicians on social media, and never take anything you can’t verify yourself as gospel, from either side.

- Are you a non-profit professional good with numbers? Good. This is your moment. Dig into everything. Post information online. Share what you find with friends.

- Keep your guard up even when things sound good on the surface. Make this organization walk the walk, not just talk the talk, when it comes to centering patrons.

- Talk about this. Push your way into the conversation.

In short, if you’re not happy about what transpires next, keep being loud. Obviously there’s never going to be any proof, but it sure feels like the orchestra has spent time and money over the last six months retooling their PR strategy to better appeal to patrons. If true, that’s fascinating. I don’t remember that ever happening before.

In the end, if you can push them just a little bit further, from name-checking you in their PR, to actually employing your input to build something sturdy and new, that every stakeholder can be excited about… Well, that might be the aversion of disaster. That might actually center the patron. That might be the start of something real.

Footnotes

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/05/arts/music/san-francisco-symphony-esa-pekka-salonen.html ↩︎

- https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/14/arts/music/esa-pekka-salonen-leaving-san-francisco-symphony.html ↩︎

- https://www.sfchronicle.com/sf/article/davies-symphony-hall-19651838.php ↩︎

- https://sfstandard.com/opinion/2024/06/20/san-francisco-symphony-troubled/ ↩︎

- https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/san-francisco-symphony-protest-ban-19550127.php ↩︎

- https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/20/arts/music/san-francisco-symphony-chorus-strike.html ↩︎

- https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/sf-symphony-2025-salonen-missing-20228326.php ↩︎

- https://www.minnpost.com/artscape/2014/08/interim-ceo-describes-changes-programming-staff-and-culture-minnesota-orchestra/ ↩︎