Forgive the Marie Hall kick, dear friends, but here’s another fantastic interview with her. As if Hall wasn’t spunky and amazing enough already, she says in this article that she wishes she could be a conductor! Even today, a hundred years later, it is relatively rare to see a woman taking on that job.

This piece is by M. Dinorben Griffith; it appeared in the Strand Magazine in June 1903.

***

“Marie is always, for ever and ever, plactising, plactising,” was the irate comment of two little boys when they failed to induce their but little older favourite sister to play with them.

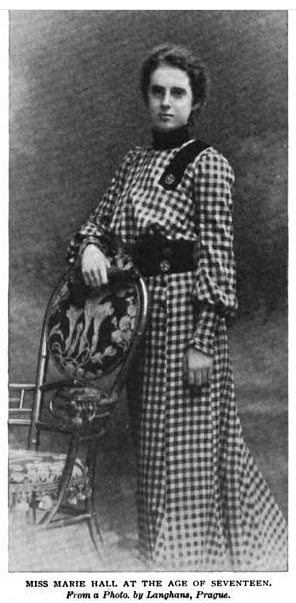

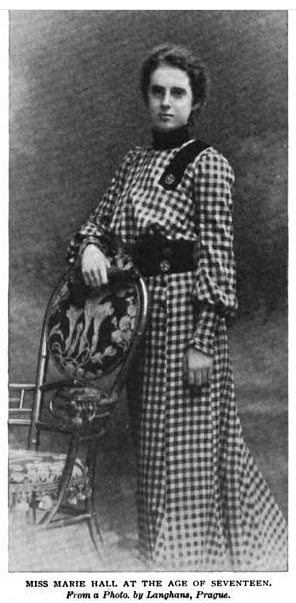

It is this “always, for ever and ever, plactising,” or, in other words, that infinite capacity for taking pains which is the sign-manual of genius, that has brought Miss Marie Hall, the girl violinist, to the front of her profession before she has reached her nineteenth birthday.

Hers is no history of that forced and most miserable of spectacles – the child prodigy, often of ephemeral life and fame. A child prodigy she undoubtedly was, but of natural growth. Her talent was discovered and fostered by strangers, and it speaks well for her bodily and mental vitality that hard work, poverty, and even sorrow have only given strength to her personality and a finished maturity to her art.

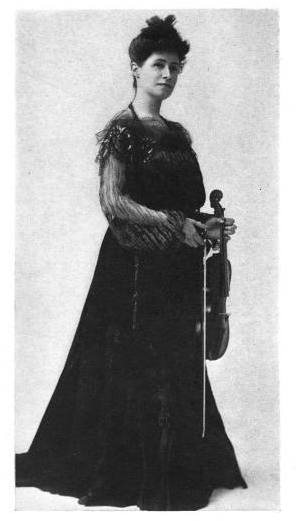

She loves her fiddle, and even when idly handling it a beautiful tenderness comes into her face, which is generally sad and grave almost to sternness. With her bow she shows her inner self to the world, at least to as much of the world as can understand its language; her clever fingers not only interpret the masterpieces of the great composers, but the longings and aspirations of a young life striving for the perfection which alone can satisfy it; and for fame, not for fame’s sake, but because it will enable her to carry out a noble, unselfish purpose.

Like all highly-strung natures her personality is complex, oftenest grave, impulsive, yet sometimes as merry and gay as a little child.

To interview her is as difficult as to follow a will-o’-the-wisp.

“Where was I born? Oh, dear, must I go back as far as that? It was ages ago! In Newcastle, on April 8th, 1884, and I was called the ‘Opera Baby.'”

“Why?”

“Because my father, Mr. Edmund Felix Hall, was harpist in the Carl Rosa English Opera Company, which toured all over England. My mother always accompanied him, and while at Newcastle I was born; the company took a great interest in this important event, and called me the ‘Opera Baby.’ I may as well go a little farther back and tell you that my grandfather was a landscape painter and a harpist; my father, his brother, my mother, and sister are all harpists, and I ought to have been one too, I suppose. I did start; but I hated it, and used to hide when my father wanted to give me a lesson. I wanted to learn the fiddle. My father had his own ideas on the subject; I had mine, and I stuck to them.”

The little lady, I noted, had more than one side to her character. Into the grave face as she spoke came a mutinous, mischievous look reminiscent of an enfant terrible. It was also easy to infer that her early childhood held no pleasant memories for her. She was one of a family of four sisters (two of whom died) and two quite young brothers, one of whom – Teddy – is the stimulus to hard work and the making and saving of money on her part. He shares his sister’s love of the fiddle, and, although not yet nine, according to Miss Hall is “much cleverer” than she.

“Teddy is a genius,” she says, enthusiastically, “but, oh, so delicate. I want to have him with me always; to get him the best advice, to care for him, educate him, and love him. That is what I have been working for, that is what success means to me.”

She started learning the harp when only five, and the violin at the age of eight and a half, her father being her first teacher. Those lessons were not shirked, they were her only pleasure. More may be learned of Miss Hall’s early days from what she leaves unsaid than what she says, but there is no doubt that when Mr. Hall left the opera company, that meant to him a regular weekly income of twelve pounds, and more especially on the termination of a short engagement at the Empire Theatre, Newcastle, the family were in dire straits. From the orchestra Mr. Hall had to come down to playing in the streets, his wife and children in turns assisting him in earning a precarious livelihood.

The struggles of those days are written on Miss Hall’s face, but the fragile little figure is linked with an indomitable will. She is of the stuff that heroes are made of, withal a very girl, with a keen sense of humour and a pretty wit of her own.

The day of her first violin lesson was an era in her baby life, for the little maid had planted her foot firmly on the first rung of the ladder of fame. She had no thought of what was to follow; she had gained her point, and it behoved her to prove that the violin was her special métier.

“One day,” she said, “I played Raff’s ‘Cavatina’ to my father. I had been practising it hard as a surprise for him.” A surprise indeed it was, for it convinced him of her ability, and she was sent to Miss Hildegarde Werner, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, for lessons. She made remarkable progress, and her teacher was so proud of her precocious little pupil that she introduced her to M. Sauret, who predicted great things of her in the near future.

“After I had been learning the violin for a year I made my first appearance on the concert platform,” said Miss Hall. “I was then about nine and a half. After the concert was over I got several offers of engagements at music-halls.”

“Did you then play in the streets?”

“Yes, we all did; I hated it.”

“What were your usual takings?”

“Oh, a penny, and up to six-pence.”

“And is it indeed indiscreet to ask what you make now?”

“I will tell you with pleasure. My first concert in London, at the St. James’s Hall, brought me in five hundred pounds.”

Four hundred people were on that occasion – her second appearance in London – turned away from the doors. A guinea was cheerfully paid for standing room, and two guineas for a seat.

Before little Marie reached her eleventh year her parents moved to Malvern, when, she pathetically remarked, “times were very bad. My sister and I had to do all the housework, as we could not afford to keep a servant, and to help by playing in the streets and in the vestibules of hotels. I used sometimes to go inside the little gardens and begin playing, and was often then called into the houses.”

“Did you dislike it?”

“I hated collecting money,” was the reply, with a flash of her eyes. “Sometimes mother went out with father and she did the collecting, while my sister and I stayed at home.”

One can easily picture that untidy ménage, with the little drudges turning out in the evenings to play for money when tired out with the hopeless task of keeping things straight at home.

“Things might have been worse, you know,” she remarked, “for several people got to know me and were very kind. Fifteen pounds was subscribed among friends to buy me a violin, but my father thought the money would be more wisely spent in taking me to London, so that Wilhelmj could hear me.”

“With what results?”

“I stayed in his house for several months, he giving me free lessons as well as keeping me. I then returned to Malvern and took up my old life; not from choice, but from necessity. I played in the streets and in hotels until I was thirteen. Herr Max Mossel heard me play and offered me free lessons, so I went to Birmingham, living with some rich friends, who paid my parents a pound a week for letting me stay during the three years I worked under Mossel.”

Herr Mossel was charmed with his pupil; he recommended her so highly to the Birmingham School of Music Committee that she received a free studentship, which she held for two sessions.

When fifteen years old she competed for the first Wessely Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Music and won it, but was unable to take it up, as she had no means to live on while in London.”

“It was such a disappointment,” said Miss Hall, “and things were worse than ever at home. We moved to Clifton, and there met with friends who were most kind to us all. They were Mr. and Mrs. Roeckel, of musical fame. We got to know them through a strange incident.

“As I told you, my uncle was a very clever harpist; he used to go about the country playing. Mr. and Mrs. Roeckel were spending a short holiday at Llandrindod Wells, in Wales. My uncle was there too, and they were delighted with his playing and spoke to him frequently, and learnt that his name was Hall.

“The Roeckels, on their return to their home at Clifton, heard one evening a harpist playing outside their door who reminded them, both in appearance and superior skill in playing, of the harpist they had met in Wales. It was his brother – my father.”

From this time their kindness was unceasing to the family, who owe much to their frequent and timely help. They took a practical interest in the clever girl violinist, and enlisted Canon Fellowes’s sympathy for their young protégée.

By Mr. Roeckel’s advice Marie got up a subscription concert, Canon Fellowes promising to bring Mr. Napier Miles, the Squire of Kings Weston, near Bristol, to hear her play. The concert was a grand success, the playing of the delicate, frail, little fifteen-year-old débutante astonishing all present.

“Wonderful! delightful!” said Mr. Napier Miles. He asked if she had ever played with an orchestra. “No,” was the reply. “Then you must come to Kings Weston for that purpose.” Her future tuition and expenses were practically assured from that day.

Mr. Miles and a few other friends combined in sending her to study under Johann Kruse, and she stayed with him a year, or until, in her own words, “I had got all he could give me.”

It was while she was in London with Kruse that she first heard Kubelik. He had shortly before been playing Bristol, and Marie had urged her father to see him and beg of him to hear her play.

“I saw,” said Miss Hall, “an announcement that he would give a recital in London on the 19th of June, 1900. I went. It was a red-letter day in my life. I went mad over his technique. As soon as the concert was over I went behind and waited outside his door, determined to see him if I had to wait until two o’ clock in the morning. After what seemed to me a long time he came out, followed by his accompanist. I rushed forward and said, ‘Oh, will you hear me play?’ He seemed very startled, drew back a little, and stammered, ‘I don’t know you, do I?’ Breathlessly I explained that my father had seen him at Bristol, and finally I left him with an appointment for ten o’ clock the next morning. I practised nearly all night, for to sleep was impossible.

“I found Kubelik and his accompanist at breakfast. I do not think they expected me; they seemed to think I was amusing, especially when I asked Kubelik to accompany me.”

With the sublime audacity of youth she had elected to play one of the very pieces she had heard Kubelik play the previous evening, the “D Minor Concerto” of Wieniawski, which was the success of the evening.

Kubelik was enthusiastic. “You must go at once,” he said, “to Prague to my old master, Sevcik.”

“But what do you think?” said Miss Hall, with a burst of merry laughter at the recollection. “Kubelik and the accompanist were so polite to me they both rushed to place a chair for me at the table, so that I could write my name and address, and I sat down – not on the chair, but on the floor, with my feet in the air and my hat – well, I don’t know where it was. I felt so small and so humiliated, and they – I do not know how they managed it – never even smiled – at least, for me to see.”

It is difficult to get Miss Hall to talk about herself. She acknowledges being a “creature of moods,” very full of spirits one moment, correspondingly despondent the next; gave, sympathetic, sedate, or a real little hoyden, full of fun and laughter.

Asked if she had received any offers of marriage since she had come out, “Two only,” was the reply – “one from a Greek, a literary man, and one from a Bohemian musician.”

“Were they nice?”

“Well,” with comically raised eyebrows, “one was old and silly, the other very young and impressionable.”

“No millionaire offers?”

“Sorry to disappoint you – no, not one.

“When did I go to Prague? Oh, very soon after my interview with Kubelik. My kind friend, Mr. Napier Miles, made all necessary arrangements. I went first to Dresden to learn a little German, which I managed to pick up without a master – Sevcik does not speak a word of English – and also to practise for my entrance examination for the Conservatoire.”

She was the great Sevcik’s only English girl pupil, and he says, “She is the most gifted pupil I have ever had.” In addition to lessons at the Conservatoire, she had private lessons as well, working often fourteen hours a day and getting up at four in the morning.

“Had you no recreation at all?”

“Oh, yes; while I was at Prague I read all Dickens’s and Thackeray’s works – to broaden my mind,” she said, with a smile. “Do you know, I am very fond of shocking people?” she added. “In Prague it is considered very improper for girls to go out alone, especially to any public place. Several girl students lived together at a pensionnat, and we English ones used to love to dress up and go and dine sometimes at an hotel; people used to look at us, shrug their shoulders, and say, ‘Es sind Englanderinen.’ I was also very fond of dancing, and learned all the Bohemian national dances, which are very pretty.”

“How long were you in Bohemia?”

“Eighteen months. A concert is given at the Conservatoire every year, in which all the students that have won their diplomas take part, and I played and was recalled twenty-five times.”

Miss Hall during her holidays once went to Marienbad, where Kubelik was also staying, and he gave her a few lessons. He has always taken a great interest in her and considers her playing marvellous. She had a grand reception at Vienna, where she gave a recital before returning to England, being recalled no fewer than five times after each piece, a great compliment from so critical an audience.

“What is your fiddle?”

“An Amati. It was lent me by my master – Sevcik – and is the one used by Kubelik when he made his début. I have no violin of my own yet, but have three bows. I think I must learn to play on them.

“A pretty incident,” Miss Hall went on to say, “occurred when I appeared for the first time after my return, at Newcastle-on-Tyne. A workman stood up and said, ‘Miss Hall ought to have a new violin. I have just made one and would like to give it to her.’ He evidently did not think much of this Amati, did he?”

“Is it not true that a violin worth two thousand guineas is being purchased by public subscription as a presentation to you?”

“Yes, it is so, but it will be some time yet before such a sum can be collected.”

I was shown a letter from Sevcik; curious – as it showed his manner of giving his pupil violin lessons by post.

“He is coming back here with me in the autumn, and I hope he will settle in London.”

“What are your plans when the season is over?”

“After my two recitals here on the 30th of May and 23rd of June, I am going back to Bohemia. I shall take a little cottage in the country there where I can have perfect quietude and devote myself to practising, for I play with Richter in Manchester next season. I have a lot to do before I can rest, though. I am booked up for a tour in the provinces.”

In March last Miss Hall was made a ward in Chancery, which, on account of family differences, her friends considered a wise measure.

“You do not know,” she said, “how I want to help my family. I have offered my parents a regular income if they will only let me have my little brother Teddy.We are so fond of each other, and I want him to get strong and well. I have offered also to have my sister in London. She is fourteen, and her great wish is to have lessons with Mr. Thomas, the Welsh harpist.”

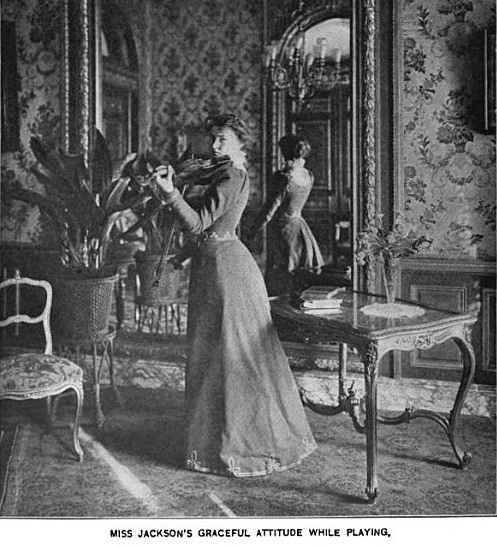

Miss Hall has very artistic tastes, is fond of pictures, and has the usual feminine love of pretty clothes. She always designs her own gowns. In a literary way her favourite books are the biographies of great musicians.

In reply to a query as to her favourite composers she said, “The three great B’s – “Bach, Brahms, Beethoven; and last, but not least, Paganini. I do not really care for anything but classical music, but the public taste must be studied too.”

She recently played for the first time before the Prince and Princess of Wales, and met with great appreciation. She is in much demand at smart “At-homes.” I heard an amusing story about a very smart society function at which she was asked to play. Her first piece was Bach’s famous “Chaconne.” When she had finished, and received the usual applause, a lady came up to her and said, “You played it divinely. It is my favourite piece. Do you play his ‘Chaconne’ also?” Miss Hall, when she had recovered a little, simply answered “Yes.”

“I forgot to tell you one thing that is important,” said Miss Marie, with a laugh. “I am immoderately fond of oranges, and eat I do not know how many a day; they taste better if I am reading a novel at the same time; that is what I was doing when you came in,” pointed to “Temporal Power” and a plate of orange peel lying side by side.

“You are a second Kubelik, people say, I hear.”

“I am not a second anybody or anything,” she quickly retorted, with a proud little gesture. “I want to be myself, with a method and style of my own. If I were a man I should like to be the conductor of an orchestra. I should love it. That is not impossible, is it? although you are unfortunate enough to be a girl.”

“Perhaps not impossible, but it would be a startling innovation, would it not?”

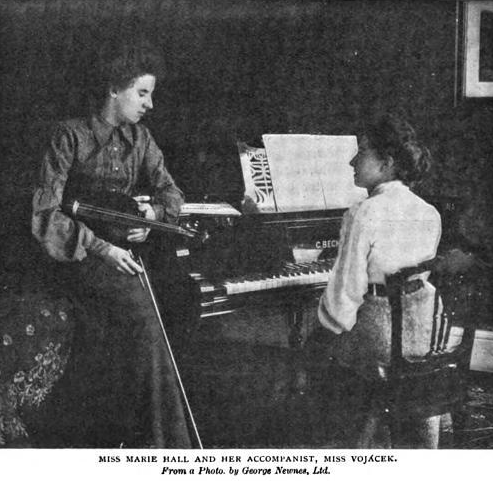

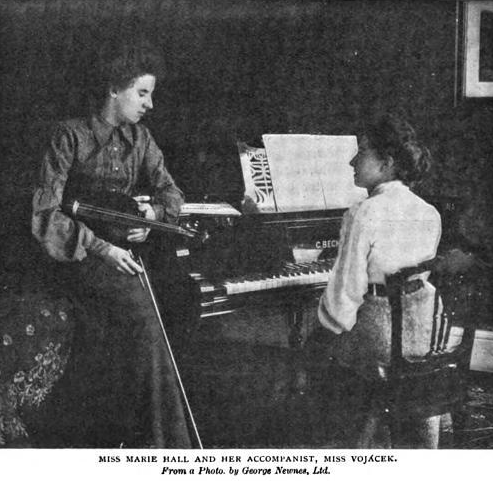

Miss Hall is fortunate in having as an accompanist a charming Bohemian lady, who was introduced to her by Sevcik himself. Miss Vojácek has travelled with, and accompanied, all the Sevcik girl pupils in England and on the Continent.

“Do not forget to mention,” said Miss Vojácek, smilingly, “that Marie always sits on the table when she is practising with me; it is so characteristic of her.”

There seems – if she does not overtax her delicate frame – to be no limit to the possibilities that the near future holds for this youthful and gifted violinist. Her short public life has been, and continues to be, a series of triumphs that might spoil a less modest and natural person.